It used to be something of an electronic rite of passage, the construction of an FM bug. Many of us will have taken a single RF transistor and a tiny coil of stiff wire, and with the help of a few passive components made an oscillator somewhere in the FM broadcast band. Connect up a microphone and you were a broadcaster, a prankster, and probably set upon a course towards a life in electronics. Back in the day such a bug might have been made from components robbed from a piece of scrap consumer gear such as a TV or VCR, and perhaps constructed spider-web style on a bit of tinplate. It wouldn’t have been stable and it certainly wouldn’t have been legal in many countries but the sense of achievement was huge.

As you might expect with a few decades of technological advancement, the science of FM bugs has moved with the times. Though you can still buy the single transistor bugs as kits there is a whole range of fancy chips designed for MP3 players that provide stable miniature transmitters with useful features such as stereo encoders. That’s not to say there isn’t scope for an updated simple bug too though, and here [James] delivers the goods with his tiny FM transmitter.

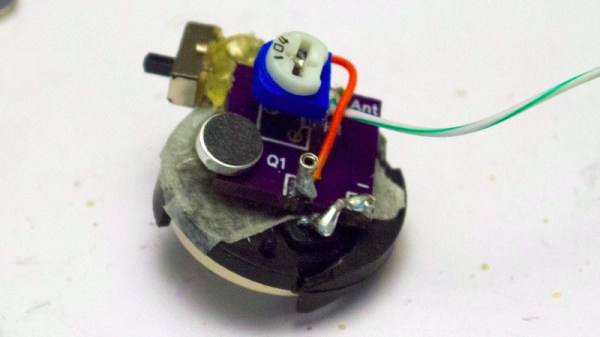

Gone is the transistor, and in its place is a MAX2606 voltage-controlled oscillator. The on-chip varicap and buffer provided by this device alleviate some of the stability issues suffered by the transistor circuits, and to improve performance further he’s added an AP2210 low-dropout regulator to catch any power-related drift. If it were ours we’d put in some kind of output network to use both sides of the differential output, but his single-ended solution at least offers simplicity. The whole is put on a board so tiny as to be dwarfed by a CR2032 cell, and we can see that a bug that size could provide hours of fun.

This may be a small and simple project, but it has found its way here for being an extremely well-executed one. It’s by no means the first FM bug we’ve shown you here, just a few are this one using scavenged SMD cellphone parts, or this more traditional circuit built on a piece of stripboard.