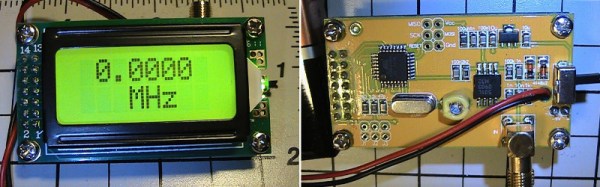

An exciting development over the last few years has been the arrival of extremely cheap instrumentation modules easily bought online and usually shipped from China. Some of them have extremely impressive paper specifications for their price, and it was one of these that caught the eye of [Carol Milazzo, KP4MD]. A frequency counter for under $14 on your favourite online retailer, and with a claimed range of 500 MHz. That could be a useful instrument in its own right, and with a range that significantly exceeds the capabilities of much more expensive bench test equipment from not so long ago.

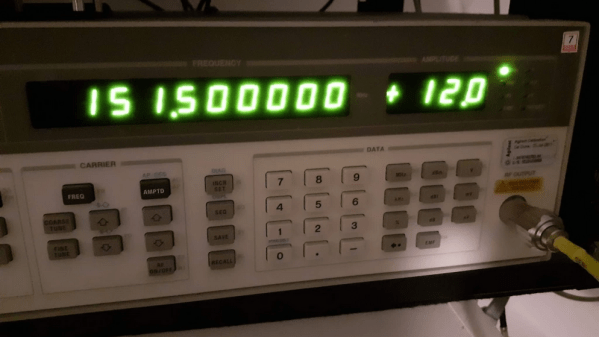

Just how good is it though, does it live up to the promise? [Carol] presents the measurements she took from the device, so you can see for yourselves. She took look at sensitivity, VSWR, and input impedance over a wide range, after first checking its calibration against a GPS-disciplined standard and making a fine adjustment with its on-board trimmer.

In sensitivity terms it’s a bit deaf, requiring 0.11 Vrms for a lock at 10 MHz. Meanwhile its input impedance decreases from 600 ohms at the bottom of its range to 80 ohms at 200 MHz, with a corresponding shift in VSWR. So it’s never going to match a high-end bench instrument from which you’d expect much more sensitivity and a more stable impedance, but for the price we’re sure that’s something you can all work around. Meanwhile it’s worth noting from the pictures she’s posted that the board has unpopulated space for an SPI interface header, which leaves the potential for it to be used as a logging instrument.

We think it’s worth having as much information as possible about components like this one, both in terms of knowing about new entrants to the market and in knowing their true performance. So if you were curious about those cheap frequency counter modules, now thanks to [Carol] you have some idea of what they can do.

While it’s convenient to buy a counter module like this one, of course there is nothing to stop you building your own. We’ve featured many over the years, this 100MHz one using a 74-series prescaler or this ATtiny offering for example, or how about this very accomplished one with an Android UI?