Hardly a week goes by that we don’t post a project where at least one commenter will lament that the hacker could have just used a 555. [Peter Monta] clearly gets that point of view. For a 555 design contest, he created both digital logic gates and an op amp, all using 555 chips. We can’t quite imagine the post apocalyptic world where the only surviving electronic components are 555 chips, but if that day were to come, [Peter] is your guy.

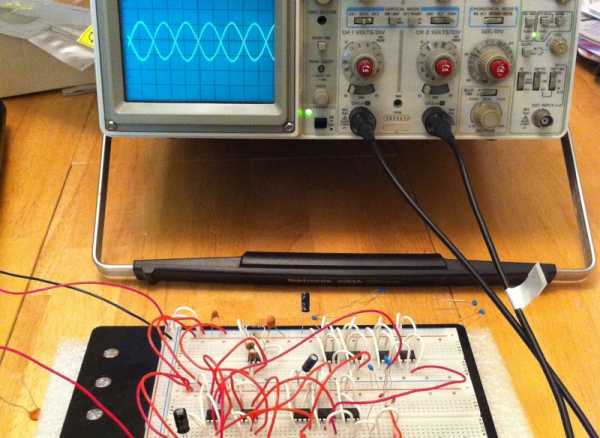

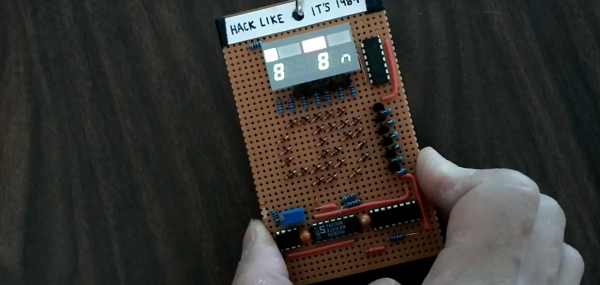

Using the internal structure of the 555, [Peter] formed a basic logic gate, an inverter, latches, and more. He also composed things like counters and seven-segment decoders. He had a very simple 4-bit CPU design in Verilog that he was going to attempt until he realized it would map into almost 400 chips (half of that if you’d use a dual 555, but still). If you built this successfully, we would probably post it, by the way. You can see a video of the digital logic counter, below.