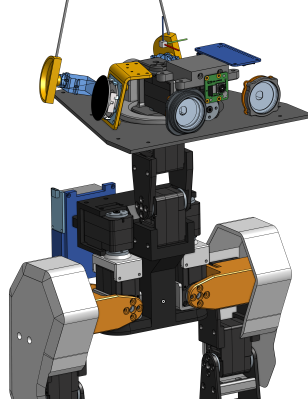

[Antoine Pirrone] and [Grégoire Passault] are making a DIY miniature re-imagining of Disney’s BDX droid design, and while it’s still early, there is definitely a lot of progress to see. Known as the Open Duck Mini v2 and coming in at a little over 40 cm tall, the project is expected to have a total cost of around 400 USD.

Bipedal robots are uncommon, and back in the day they were downright rare. One reason is that the state of controlled falling that makes up a walking gait isn’t exactly a plug-and-play feature.

Walking robots are much more common now, but gait control for legged robots is still a big design hurdle. This goes double for bipeds. That brings us to one of the interesting things about the Open Duck Mini v2: computer simulation of the design is playing a big role in bringing the project into reality.

It’s a work in progress but the repository collects all the design details and resources you could want, including CAD files, code, current bill of materials, and links to a Discord community. Hardware-wise, the main work is being done with very accessible parts: Raspberry Pi Zero 2W, fairly ordinary hobby servos, and an BNO055-based absolute orientation IMU.

So, how far along is the project? Open Duck Mini v2 is already waddling nicely and can remain impressively stable when shoved! (A “testing purposes” shove, anyway. Not a “kid being kinda mean to your robot” shove.)

Check out the videos to see it in action, and if you end up making your own, we want to hear about it, so remember to send us a tip!