Students of the Samara State Aerospace University are having trouble getting a signal from their satellite, SamSat-218D. They are now reaching out to the radio amateur community, inviting everybody with sufficiently sensitive UHF VHF band (144 MHz) equipment to help by listening to SamSat-218D. The satellite was entirely built by students and went into space on board of a Soyuz-2 rocket on April 26, 2016. This is their call (translated by Google):

Analog To Digital Converter (ADC): A True Understanding

Back in the day where the microprocessor was our standard building block, we tended to concentrate on computation and processing of data and not so much on I/O. Simply put there were a lot of things we had to get working just so we could then read the state of an I/O port or a counter.

Nowadays the microcontroller has taken care of most of the system level needs with the luxury of built in RAM memory and the ability to upload our code. That leaves us able to concentrate on the major role of a microcontroller: to interpret something about the environment, make decisions, and often output the result to energize a motor, LED, or some other twiddly bits.

Often the usefulness of a small microcontroller project depends on being able to interpret external signals in the form of voltage or less often, current. For example the output of a photocell, or a temperature sensor may use an analog voltage to indicate brightness or the temperature. Enter the Analog to Digital Converter (ADC) with the ability to convert an external signal to a processor readable value.

Continue reading “Analog To Digital Converter (ADC): A True Understanding”

Screw Drive Tractor Is About To Conquer Canada

The incredible screw drive tractor is back. We’ve covered the previous test ride, which ended with a bearing pillow block ripping in half, but since then, again, a lot of repair work has been done. [REDNIC79] reinforced the load-bearing parts and put on a fresh pair of “tires”. The result is still as unbelievable as the previous versions, but it now propels itself forward at a blazing 3 mph (this time without tearing itself apart).

[REDNIC79] walks us through all the details of the improvements he made since the first version. After the last failure, he figured, that a larger screw pod diameter would give the vehicle a better floatation while smaller thread profile would prevent the screws from digging too deep into the ground, thus reducing the force required to move the vehicle forward.

[REDNIC79] walks us through all the details of the improvements he made since the first version. After the last failure, he figured, that a larger screw pod diameter would give the vehicle a better floatation while smaller thread profile would prevent the screws from digging too deep into the ground, thus reducing the force required to move the vehicle forward.

[REDNIC79] found four identical 100 pounds, 16 inch diameter propane tanks to build the new pods from. The tanks were a bit too short for the tractor, so he cut open two of the tanks and used them to extend the other two before welding a double thread screw onto each. He also tapered the front ends of the tanks to make the ride even smoother. After mounting the new pods to the speedster, a pair of custom steel chain guards were added to prevent rocks from getting into the chain. And then, it was time for another test ride. Enjoy the video:

Continue reading “Screw Drive Tractor Is About To Conquer Canada”

35 MPH NERF Darts!

Did you know the muzzle velocity of a NERF dart out of a toy gun? Neither did [MJHanagan] until he did all sorts of measurement. And now we all know: between 35 and 40 miles per hour (around 60 km/h).

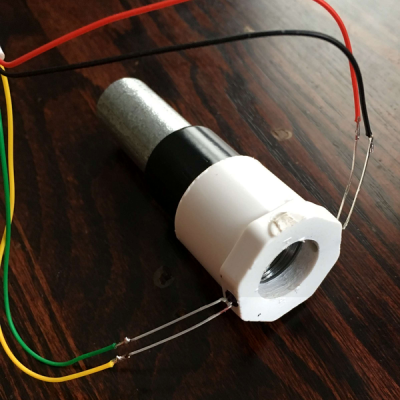

First, he prototyped a single beam-break detector (shown above) and then expanded his build to two in order to get velocity info. A Propeller microcontroller took care of measuring the timing. Then came the gratuitous statistics. He took six different darts and shot them each 21 times, recording the timings. Dart #3 was the winner, but they all had similar average speeds. You’re not going to win the office NERF war by cherry-picking darts.

First, he prototyped a single beam-break detector (shown above) and then expanded his build to two in order to get velocity info. A Propeller microcontroller took care of measuring the timing. Then came the gratuitous statistics. He took six different darts and shot them each 21 times, recording the timings. Dart #3 was the winner, but they all had similar average speeds. You’re not going to win the office NERF war by cherry-picking darts.

Anyway, [MJ] and his son had a good time testing them out, and he thinks this might make a good kids’ intro to science and statistics. We think that’s a great idea. You won’t be surprised that we’ve covered NERF chronographs before, but this implementation is definitely the scienciest!

Thanks [drudrudru] for the tip!

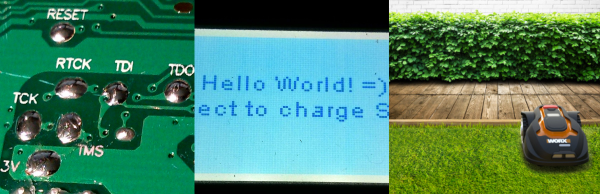

Reverse Engineer Your Robot Lawnmower

Your home is your castle, and you are king or queen of all you survey. You’ve built your own home-automation system from scratch. Why would you possibly settle for the stock firmware in your robotic lawnmower? [Daniel Wiegert] wouldn’t either, so in Project Landlord he has started to reverse-engineer it.

You can hardly blame him. The Worx Landroid‘s controller board uses an NXP LPC1768 ARM Cortex-M3, and the debug pins are labelled on the backside. The manufacturer didn’t protect the flash memory. It’s just begging to have its firmware dumped. So far, [Daniel] has managed to both brick and unbrick the device, and has completely mapped the controller’s pinout, so he’s on his way to complete control.

Right now, he’s got a working proof-of-concept firmware on his GitHub that’s able to drive the machine around a little bit and set the brakes. It’s running FreeRTOS, and [Daniel] is looking for other people to get in on the project. He’s done the hard initial work, so get in there and reap the rewards! Just don’t neglect to remove the blade before custom firmware.

Will custom firmware in a robotic lawnmower change the world? Probably not. But it is awesome, and will certainly make a difference in the lives of people whose robot mowers continually get stuck behind the hydrangeas.

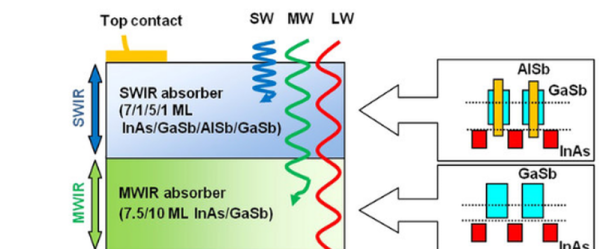

Infrared Detector Selects Over A Wide Range

You can classify infrared light into three broad ranges: short wave, medium wave, and long wave. Traditionally, sensors concentrate on one or two bands, and each band has its own purpose. Short wave IR, for example, produces images similar to visible light images. Long wave is good for thermal imaging.

Researchers have announced a new detector that, by adjusting a bias, can detect all three bands using a simple approach that stacks different absorption layers over a semiconductor substrate. The device only requires two terminals and is very efficient, although the efficiency varies based on the band.

We’ve covered infrared sensing before. We’ve even seen DSLRs hacked into IR sensors. This new research might be a bit much to duplicate in your garage. After all, it requires tellurium doped gallium antimonide substrates and sophisticated processing equipment. However, this research will probably lead to practical devices that will find their way into projects before too long.

What’s The Weather Like For The Next Six Hours?

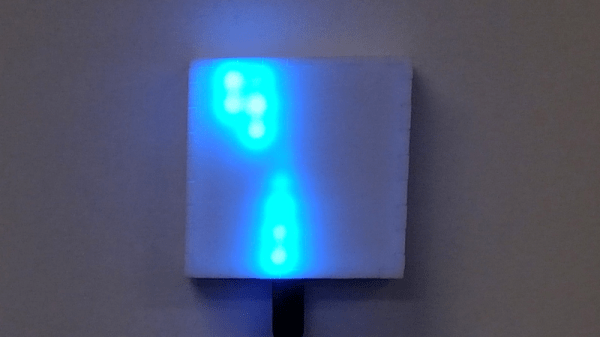

The magic glowing orb that tells the future has been a popular thing to make ever since we realized we had the technology to bring it out of the fortune teller’s tent. We really like [jarek319]’s interpretation of the concept.

Sitting mystically above his umbrella stand, with a single black cord providing the needed pixies for fortune telling, a white cube plays an animation simulating the weather outside for the next six hours. If he sees falling drops, he knows to grab an umbrella before leaving the house. If he sees a thunderstorm, he knows to get the umbrella with the fiberglass core in order to prevent an intimate repeat of Mr. Franklin’s early work.

Continue reading “What’s The Weather Like For The Next Six Hours?”