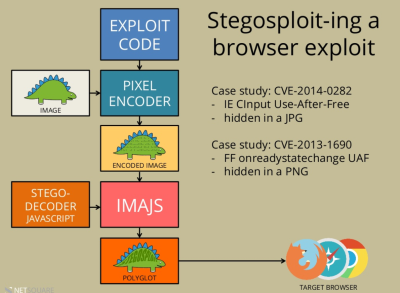

We’re primarily hardware hackers, but every once in a while we see a software hack that really tickles our fancy. One such hack is Stegosploit, by [Saumil Shah]. Stegosploit isn’t really an exploit, so much as it’s a means of delivering exploits to browsers by hiding them in pictures. Why? Because nobody expects a picture to contain executable code.

[Saumil] starts off by packing the real exploit code into an image. He demonstrates that you can do this directly, by encoding characters of the code in the color values of the pixels. But that would look strange, so instead the code is delivered steganographically by spreading the bits of the characters that represent the code among the least-significant bits in either a JPG or PNG image.

[Saumil] starts off by packing the real exploit code into an image. He demonstrates that you can do this directly, by encoding characters of the code in the color values of the pixels. But that would look strange, so instead the code is delivered steganographically by spreading the bits of the characters that represent the code among the least-significant bits in either a JPG or PNG image.

OK, so the exploit code is hidden in the picture. Reading it out is actually simple: the HTML canvas element has a built-in getImageData() method that reads the (numeric) value of a given pixel. A little bit of JavaScript later, and you’ve reconstructed your code from the image. This is sneaky because there’s exploit code that’s now runnable in your browser, but your anti-virus software won’t see it because it wasn’t ever written out — it was in the image and reconstructed on the fly by innocuous-looking “normal” JavaScript.

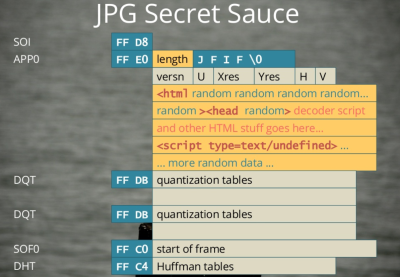

And here’s the coup de grâce. By packing HTML and JavaScript into the header data of the image file, you can end up with a valid image (JPG or PNG) file that will nonetheless be interpreted as HTML by a browser. The simplest way to do this is send your file

And here’s the coup de grâce. By packing HTML and JavaScript into the header data of the image file, you can end up with a valid image (JPG or PNG) file that will nonetheless be interpreted as HTML by a browser. The simplest way to do this is send your file myPic.JPG from the webserver with a Content-Type: text/html HTTP header. Even though it’s a totally valid image file, with an image file extension, a browser will treat it as HTML, render the page and run the script it finds within.

The end result of this is a single image that the browser thinks is HTML with JavaScript inside it, which displays the image in question and at the same time unpacks the exploit code that’s hidden in the shadows of the image and runs that as well. You’re owned by a single image file! And everything looks normal.

We like this because it combines two sweet tricks in one hack: steganography to deliver the exploit code, and “polyglot” files that can be read two ways, depending on which application is doing the reading. A quick tag-search of Hackaday will dig up a lot on steganography here, but polyglot files are a relatively new hack.

[Ange Ablertini] is the undisputed master of packing one file type inside another, so if you want to get into the nitty-gritty of [Ange]’s style of “polyglot” file types, watch his talk on “Funky File Formats” (YouTube). You’ll never look at a ZIP file the same again.

Sweet hack, right? Who says the hardware guys get to have all the fun?