TI makes some great chips, and to sell those chips, they’re more than willing to put together some awesome tutorials, examples, and online classes to get engineers up and running. This isn’t limited to $5 Launchpads; TI has a great video and lab series for their precision OpAmps. These tutorials come with an evaluation module that costs about $200. Yes, that’s two Benjamins for a few OpAmps and a PCB. Of course no engineer would ever pay this; their job would. But what about someone who wants to learn at home?

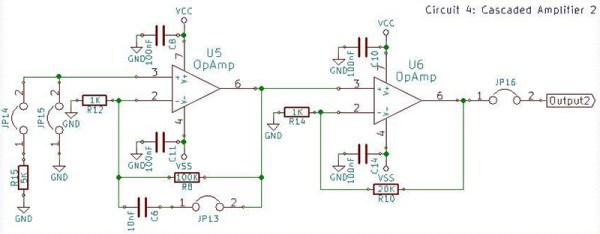

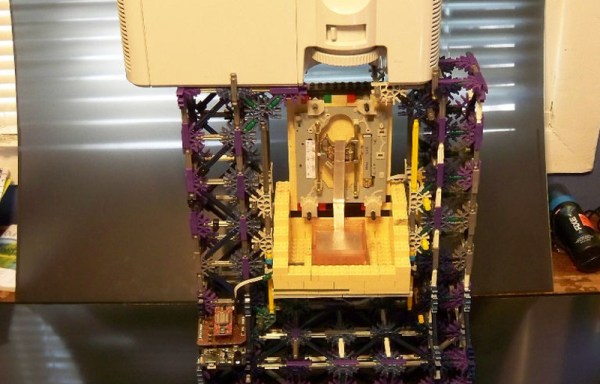

That’s where [SUF]’s project for The Hackaday Prize comes in. He’s building a replica of a $200 lab board, and even without researching the cheapest solution for each individual component, [SUF] reckons he can build this kit for about $50. Like I said, the TI board is a business purchase.

The complete lab and tutorial TI offers uses NI’s virtual lab. This, again, isn’t something a random electron hacker could afford, but anyone who wants to go through this teaching module would probably use their own tools anyway.

As far as projects to teach electronics go, [SUF] has knocked it out of the park. He’s already relying on excellent tutorials, but bringing the price down to something a little more sane and amenable to checkbooks that aren’t tied to the corporate account.