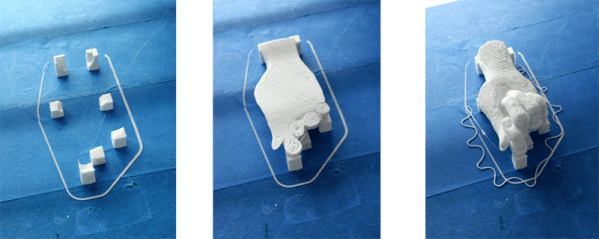

[ekaggrat] designed a 3d-printed clock that’s fairly simple to make and looks awesome. The clock features a series of 3d-printed gears, all driven by a single stepper motor that [ekaggrat] found in surplus.

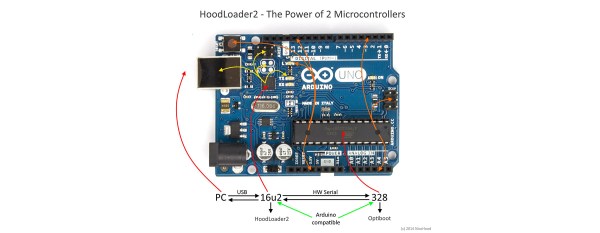

The clock’s controller is based around an ATtiny2313 programmed with the Arduino IDE. The ATtiny controls a Darlington driver IC which is used to run the stepper motor. The ATtiny drives the stepper motor forward every minute, which moves both the hour and minute hands through the 3d-printed gears. The hour and minute are indicated by two orange posts inside the large gears.

[ekaggrat] etched his own PCB for the microcontroller and stepper driver, making the build nice and compact. If you want to build your own, [ekaggrat] posted all of his design files on GitHub. All you need is a PCB (or breadboard), a few components, and a bit of time on a 3D printer to make your own clock.