In the beginning, there was the BIOS, and it was good. A PC’s BIOS knows how to set up the different hardware devices, grab a fixed part of a hard drive, load it, and run it. That’s all you need. While it might be all you need, it isn’t everything people want, so a consortium developed UEFI, which can do all the things a normal BIOS can’t. Among other things, UEFI can load code for the operating system over the network instead of from the hard drive.

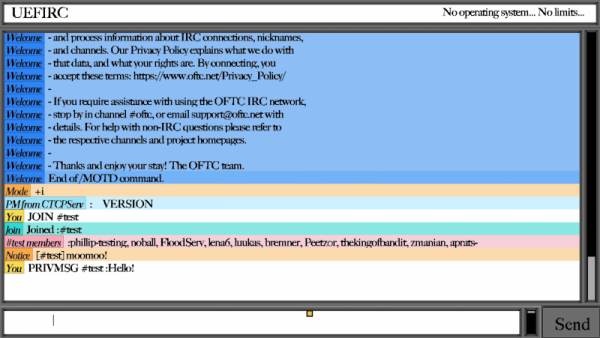

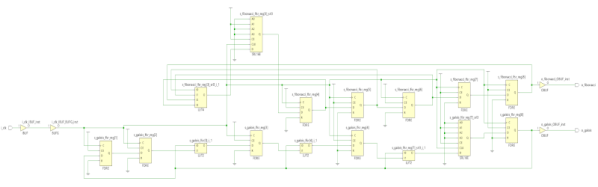

In true hacker fashion, [Phillip Tennen] thought, “Does it have to be an operating system?” The answer, of course, is no. It could be an IRC client. He chose Rust to implement everything. While UEFI does provide a network stack, it isn’t very easy to use, apparently. It also provides support for a mouse. [Phillip] ported his GUI toolkit library over, and then the rest is just building an IRC client.

The client isn’t the easiest to use because, after all, this is a lark. Why would you want to do this? On the other hand, we can think of reasons we might want to take control of a UEFI motherboard and use it for something. If you want to do that, this project is a great template to jump-start your endeavors.

We’ve looked at the UEFI system a few times. Or, you can use it to play DOOM.