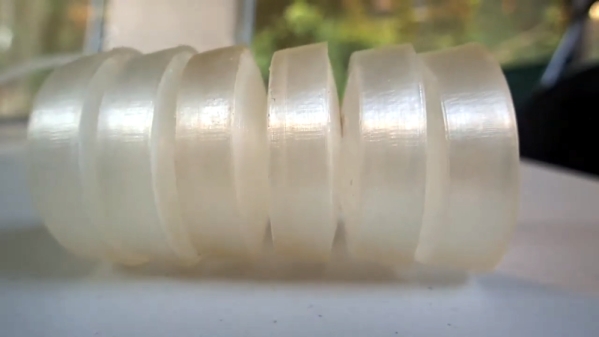

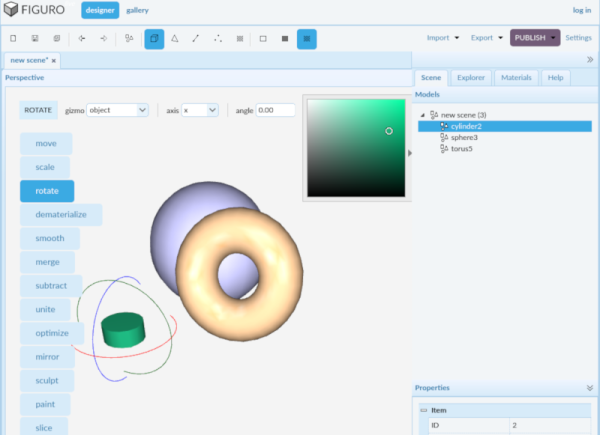

The biggest problem with fused deposition 3D prints is that while the layers should stick together, they aren’t the same as a solid piece of plastic you would get from, say, injection molding. You can anneal plastic using moderate heat, but it is likely to cause the part to deform or change size. [Free Spirit 1] has a solution for this. Using a powdered salt, the part is packed on the inside and out and put in an oven. The results in the video below look really impressive.

In addition to making the part look solid and — we assume — adding strength, the resulting prints are also water- and gas-tight which was the purpose of the effort. That alone would make the technique worthwhile.

The only thing we noticed is that the part has to have access to hold the salt. Anything not supported would be subject to deformation. However, the ground-up salt is so fine that it should be relatively easy to fill in most parts and, of course, print with 100% infill to avoid hollow internal areas.

[Free spirit 1] used a coffee grinder to get the salt powder, but apparently you can buy “flour salt.” We wondered if other powders might work well, too. Apparently, sand didn’t work out, perhaps because the salt dissolves out in water, so whatever you use, it should probably dissolve in something that won’t attack your plastic.

Annealing isn’t a new idea, and we’d love to see some objective tests on this new method.

Continue reading “Reforming 3D Prints With Salt And Heat” →