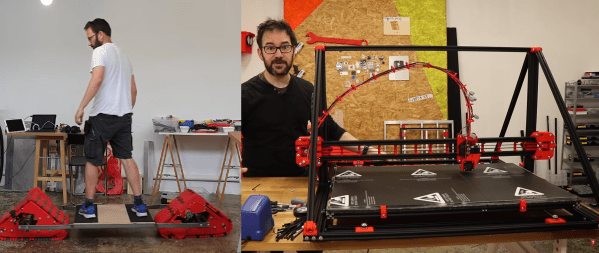

If you’re serious about engineering the things you build, you need to know the limits of the materials you’re working with. One important way to characterize materials is to test the tensile strength — how much force it takes to pull a sample to the breaking point. Thankfully, with the right hardware, this is easy to measure and [CrazyBlackStone] has built a rig to do just that.

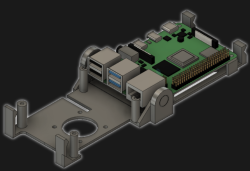

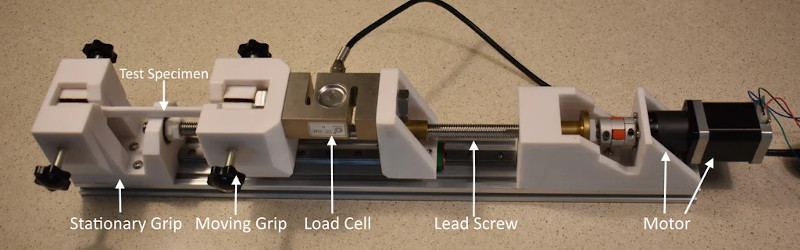

Built on a frame of aluminium extrusion, a set of 3D printed parts to hold everything in place. To apply the load, a stepper motor is used to slowly turn a leadscrew, pulling on the article under test. Tensile forces are measured with a load cell hooked up to an Arduino, which reports the data back to a PC over its USB serial connection.

It’s a straightforward way to build your first tensile tester, and would be perfect for testing 3D printed parts for strength. The STEP files (13.4 MB direct download) for this project are available, but [CrazyBlackStone] recommends waiting for version two which will be published this fall on Thingiverse although we didn’t find a link to that user profile.

Now we’ll be able to measure tensile strength, but the stiffness of parts is also important. You might consider building a rig to test that as well. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Tensile Testing Machine Takes 3D Printed Parts To The Breaking Point”

After seeing the poorly embossed paper maps used in the school, [Sergei] decided there had to be a better way. The solution was 3D printing, which makes producing a map with physical contours easy. Initial attempts involved printing street maps and world maps with raised features, such that students could feel the lines rather than seeing them.

After seeing the poorly embossed paper maps used in the school, [Sergei] decided there had to be a better way. The solution was 3D printing, which makes producing a map with physical contours easy. Initial attempts involved printing street maps and world maps with raised features, such that students could feel the lines rather than seeing them.