Over a decade after the last Star Trek show warped off of television, we finally have a new series in the form of Star Trek: Discovery. But much to the chagrin of many old school Trek fans, Discovery has gone all in on the gritty and hyper-serialized storytelling that’s taken over TV since Starfleet last patrolled the airwaves. But for those who are looking for somewhat more lighthearted space adventures, Seth MacFarlane (of Family Guy fame) has created a show which is essentially a love-letter to Star Trek: The Next Generation called The Orville. Some have gone as far as to claim that The Orville is the true continuation of the Trek legacy, though such discussion sounds awfully close to a Holy War to us so we’ll steer clear.

Unfortunately for The Orville fans, the series doesn’t have nearly the commercial draw of Trek. Accordingly, the market for things like replica uniforms and props from the show is still in its infancy, meaning fans of the show have to go the DIY route. [JohnSmallBerries] is one such fan, and his 3D printed “Comscanner” from The Orville is a shot across the bow to the well established Trek prop-making scene.

Unfortunately for The Orville fans, the series doesn’t have nearly the commercial draw of Trek. Accordingly, the market for things like replica uniforms and props from the show is still in its infancy, meaning fans of the show have to go the DIY route. [JohnSmallBerries] is one such fan, and his 3D printed “Comscanner” from The Orville is a shot across the bow to the well established Trek prop-making scene.

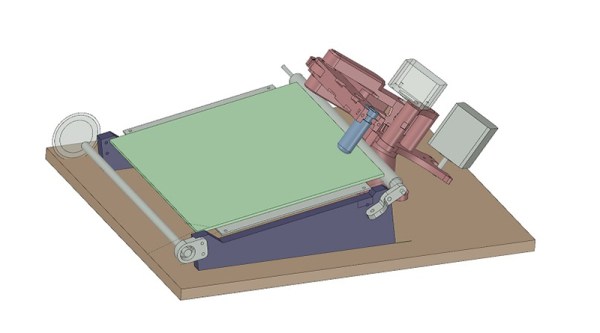

Without so much as an official toy version of the device, [John] was forced to do his initial 3D rendering based completely on screenshots from the show. Even the scale of the device had to be guessed, as it’s usually only seen being held in a crew member’s hand. In the end he reasoned it’s probably supposed to be about the size of a large smartphone.

Not content with just a static prop, [John] managed to integrate not only the spring-assisted retractable display of the scanner from the show, but also some LED backlit panels complete with a screen-accurate user interface. Judging by the internal shots of the scanner, it looks like there’s still plenty of room inside to add some more advanced electronics. The next evolution of this prop will surely be to add in a microcontroller and potentially even a real screen to add some more elaborate effects and (relatively) practical functions.

We’ve seen plenty of impressive builds of Star Trek gadgets, arguably bringing the devices much closer to reality than the original show runners ever did. It will be interesting to see if The Orville inspires a new generation of engineers to bring their favorite fictional pieces of kit into the real world.