Here at Hackaday, we love clever 3D prints. This amazing lion statue remixed by [ _primoz_], makes us feel no different. It is no secret that FDM 3D printers have come a long way, propelled by the enthusiastic support from the open source community.

However, FDM 3D printers have some inherent limitations; some of which arise from a finite print nozzle diameter, tracing out the 3D object layer by layer. Simply put, some print geometries and dimensions are just unattainable. We discussed the solution to traditional FDM techniques being confined to Planer layers only in a previous article.

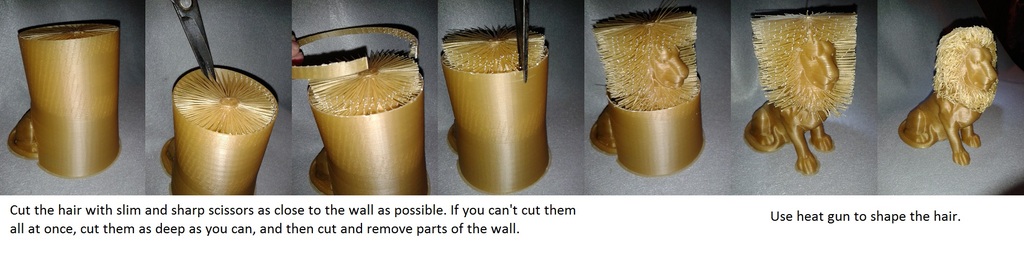

The case in point here is a 3D printed lion whose original version did not fully capture its majestic mane. [_primoz_] solution was to construct a support cylinder around the head and form the actual hair as a series of planar bristles, which were one extrusion wide.

This was followed by some simple post processing, where a heat gun was used to form the bristles into a dapper mane.

The result is rather glorious and we can’t wait for someone to fire up a dual extruder and bring out the flexible filament for this print!

[via Thingiverse]