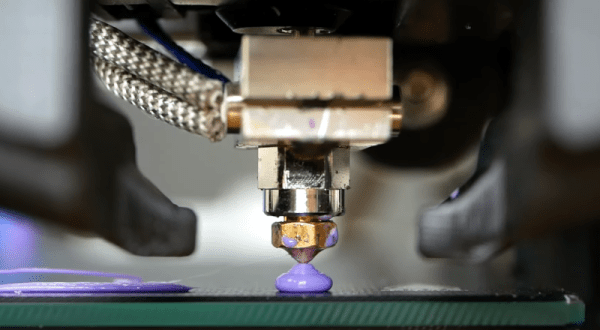

PrusaSlicer has a new feature: the ability to import a CAD model for 3D printing. Starting in version 2.5.0-beta1, PrusaSlicer can import STEP format 3D models. An imported STEP file is converted to a triangle mesh on import (making it much like a typical .stl or .3mf file) which means that slicing all happens as one would normally expect. This is pretty exciting news, because one is not normally able to drop a CAD format 3D model directly into a slicer. With this change, one can now drag .stp or .step files directly into PrusaSlicer for printing.

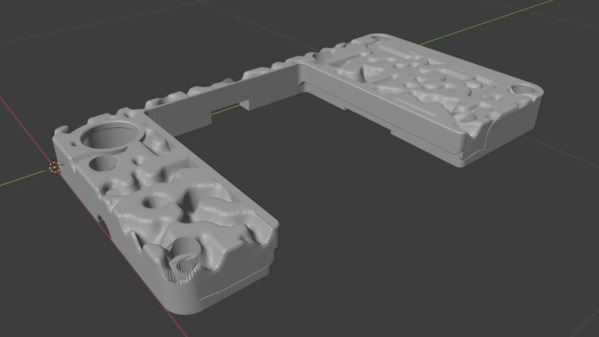

First, a brief recap. In the world of 3D models there are two basic kinds: meshes and CAD models. The two work very differently, especially when it comes to editing. 3D printing has a long history of using .stl files (which are meshes) but making engineering-type changes to such files is difficult. Altering the size of a thread or changing mounting holes in a CAD model is easy. On an STL, it is not. This leads to awkward workarounds when engineering-type changes are needed on STLs. STEP, on the other hand, is a format widely supported by CAD programs, and can now be understood by PrusaSlicer directly. Continue reading “PrusaSlicer Now Imports STEP Files, Here’s Why That’s A Big Deal”