There are a lot of ways that metals can be formed into various shapes. Forging, casting, and cutting are some methods of getting the metal in the correct shape. An oft-overlooked aspect of smithing (at least by non-smiths) is the effect of temperature on the final characteristics of the metal, such as strength, brittleness, and even color. A smith may dunk a freshly forged sword into a bucket of oil or water to make the metal harder, or a craftsman with a drill bit might treat it with an extremely cold temperature to keep it from wearing out as quickly.

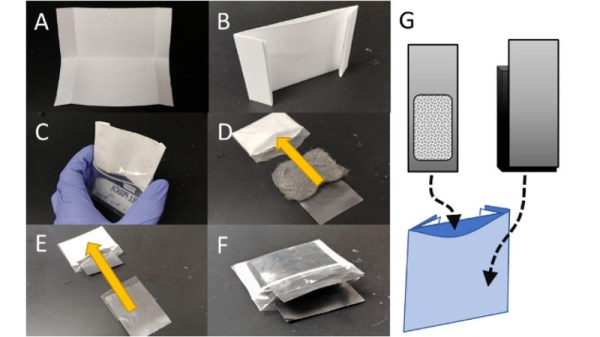

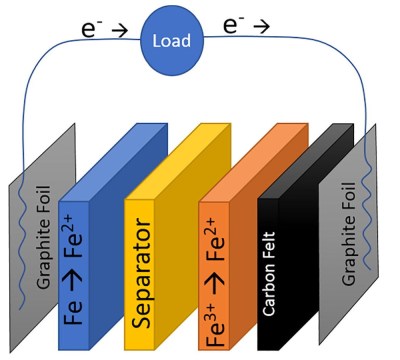

Welcome to the world of cryogenic treatment. Unlike quenching, where a hot metal is quickly cooled to create a hard crystal structure in the metal, cryogenic treatment is done by cooling the metal off slowly, and then raising it back up to room temperature slowly as well. The two processes are related in that they both achieve a certain amount of crystal structure formation, but the extreme cold helps create even more of the structure than simply tempering and quenching it does. The crystal structure wears out much less quickly than untreated steel, therefore the bits last much longer.

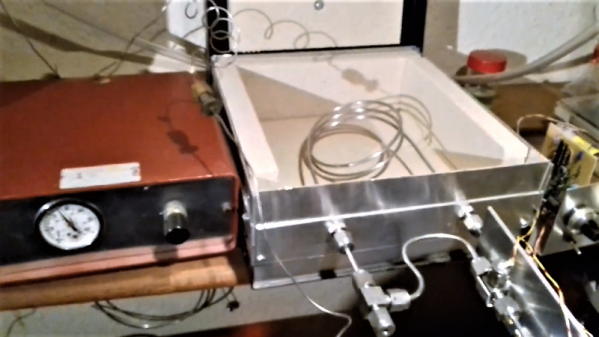

[Applied Science] goes deep into the theory behind these temperature treatments on the steel, and the results speak for themselves. With the liquid nitrogen treatments the bits were easily able to drill double the number of holes on average. The experiment was single-blind too, so the subjectivity of the experimenter was limited. There’s plenty to learn about heat-treated metals as well, even if you don’t have a liquid nitrogen generator at home.

Thanks to [baldpower] for the tip!

Continue reading “Reducing Drill Bit Wear The Cryogenic Way”