Most of us probably have a vision of how “The Robots” will eventually rise up and deal humanity out of the game. We’ve all seen that movie, of course, and know exactly what will happen when SkyNet becomes self-aware. But for those of you thinking we’ll get off relatively easy with a quick nuclear armageddon, we’re sorry to bear the news that AI seems to have other plans for us, at least if this report of dodgy AI-generated mushroom foraging manuals is any indication. It seems that Amazon is filled with publications these days that do a pretty good job of looking like they’re written by human subject matter experts, but are actually written by ChatGPT or similar tools. That may not be such a big deal when the subject matter concerns stamp collecting or needlepoint, but when it concerns differentiating edible fungi from toxic ones, that’s a different matter. The classic example is the Death Cap mushroom (Amanita phalloides) which varies quite a bit in identifying characteristics like color and size, enough so that it’s often tough for expert mycologists to tell it apart from its edible cousins. Trouble is, when half a Death Cap contains enough toxin to kill an adult human, the margin for error is much narrower than what AI is likely to include in a foraging manual. So maybe that’s AI’s grand plan for humanity — just give us all really bad advice and let Darwin take care of the rest.

fungi8 Articles

Unconventional Computing Laboratory Grows Its Own Electronics

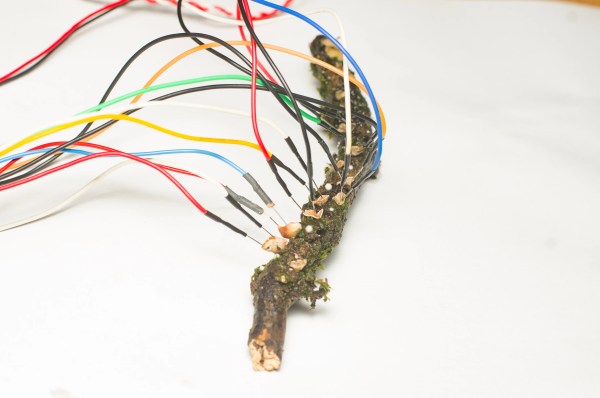

While some might say we’re living in a cyberpunk future already, one technology that’s conspicuously absent is wetware. The Unconventional Computing Laboratory is working to change that.

Previous work with slime molds has shown useful for spatial and network optimization, but mycelial networks add the feature of electrical spikes similar to those found in neurons, opening up the possibility of digital computing applications. While the work is still in its early stages, the researchers have already shown how to create logic gates with these fantastic fungi.

Long-term, lead researcher [Andrew Adamatzky] says, “We can say I’m planning to make a brain from mushrooms.” That goal is quite awhile away, but using wetware to build low power, self-repairing fungi devices of lower complexity seems like it might not be too far away. We think this might be applicable to environmental sensing applications since biological systems are likely to be sensitive to many of the same contaminants we humans care about.

We’ve seen a other efforts in myceliotronics, including biodegradable PCB substrates and attempts to send sensor signals through a mycelial network.

Via Tom’s Hardware.

MycelioTronics: Biodegradable Electronics Substrates From Fungi

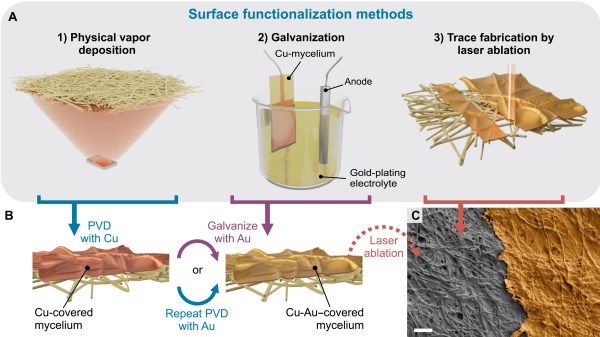

E-waste is one of the main unfortunate consequences of the widespread adoption of electronic devices, and there are various efforts to stem the flow of this pernicious trash. One new approach from researchers at the Johannes Kepler University in Austria is to replace the substrate in electronics with a material made from mycelium skins.

Maintaining performance of ICs and other electronic components in a device while making them biodegradable or recyclable has proved difficult so far. The substrate is the second largest contributor (~37% by weight) to the e-waste equation, so replacing it with a more biodegradable solution would still be a major step toward a circular economy.

To functionalize the mycelial network as a PCB substrate, the network is subjected to Physical Vapor Deposition of copper followed by deposition of gold either by more PVD or electrodeposition. Traces are then cut via laser ablation. The resulting substrate is flexible and can withstand over 2000 bending cycles, which may prove useful in flexible electronics applications.

If you’re looking for more fun with fungi, check out these mycelia bricks, this fungus sound absorber, or this mycellium-inspired mesh network.

Automated Mushroom Cultivation Yields Delicious Fried Goodies

[Kyle Gabriel] knows mushrooms, and his years of experience really shine through in his thorough documentation of an automated mushroom cultivation environment, created with off-the-shelf sensors and hardware as much as possible. The results speak for themselves, with some delicious fried oyster mushrooms to show for it!

The most influential conditions for mushroom cultivation are temperature, humidity, and CO2 concentration, and to automate handling the environmental conditions [Kyle] created Mycodo, an open-source system that leverages inexpensive hardware and parts while also having the ability to take regular photos to keep an eye on things.

Calling [Kyle]’s documentation “comprehensive” doesn’t do it justice, and he addresses everything from setting up a positive pressure air filtration system for a work area, to how to get usable cultures from foraged mushrooms, all the way through growth and harvesting. He even includes a delicious-looking recipe for fried mushrooms. It just doesn’t get more comprehensive than that.

We’ve seen [Kyle]’s earlier work before, and it’s fantastic to see the continued refinement. Check out a tour of the whole thing in the video embedded below (or skip to 16:11 if you want to make yourself hungry.)

Continue reading “Automated Mushroom Cultivation Yields Delicious Fried Goodies”

There’s A Fungus Among Us That Absorbs Sound And Does Much More

Ding dong, the office is dead — at least we hope it is. We miss some of the people, the popcorn machine, and the printer most of all, but we say good riddance to the collective noise. Thankfully, we never had to suffer in an open office.

For many of us, yours truly included, home has become the place where we spend approximately 95% of our time. Home is now an all-purpose space for work, play, and everything in between, like anxiety-induced online shopping. But unless you live alone in a secluded area and/or a concrete bunker, there are plenty of sound-based distractions all day and night that emanate from both inside and outside the house. Headphones are a decent solution, but wearing them isn’t always practical and gets old after a while. Wouldn’t it be nice to be able to print your own customized sound absorbers and stick them on the walls? Continue reading “There’s A Fungus Among Us That Absorbs Sound And Does Much More”

Build A Fungus Foraging App With Machine Learning

As the 2019 mushroom foraging season approaches it’s timely to combine my thirst for knowledge about low level machine learning (ML) with a popular pastime that we enjoy here where I live. Just for the record, I’m not an expert on ML, and I’m simply inviting readers to follow me back down some rabbit holes that I recently explored.

But mushrooms, I do know a little bit about, so firstly, a bit about health and safety:

But mushrooms, I do know a little bit about, so firstly, a bit about health and safety:

- The app created should be used with extreme caution and results always confirmed by a fungus expert.

- Always test the fungus by initially only eating a very small piece and waiting for several hours to check there is no ill effect.

- Always wear gloves – It’s surprisingly easy to absorb toxins through fingers.

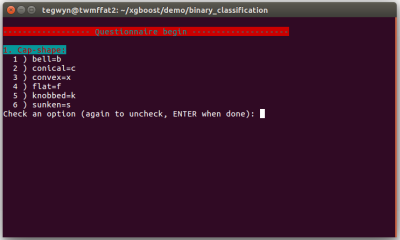

Since this is very much an introduction to ML, there won’t be too much terminology and the emphasis will be on having fun rather than going on a deep dive. The system that I stumbled upon is called XGBoost (XGB). One of the XGB demos is for binary classification, and the data was drawn from The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mushrooms. Binary means that the app spits out a probability of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and in this case it tends to give about 95% probability that a common edible mushroom (Agaricus campestris) is actually edible.

The app asks the user 22 questions about their specimen and collates the data inputted as a series of letters separated by commas. At the end of the questionnaire, this data line is written to a file called ‘fungusFile.data’ for further processing.

XGB can not accept letters as data so they have to be mapped into ‘classic LibSVM format’ which looks like this: ‘3:218’, for each letter. Next, this XGB friendly data is split into two parts for training a model and then subsequently testing that model.

Installing XGB is relatively easy compared to higher level deep learning systems and runs well on both Linux Ubuntu 16.04 and on a Raspberry Pi. I wrote the deployment app in bash so there should not be any additional software to install. Before getting any deeper into the ML side of things, I highly advise installing XGB, running the app, and having a bit of a play with it.

Training and testing is carried out by running bash runexp.sh in the terminal and it takes less than one second to process the 8124 lines of fungal data. At the end, bash spits out a set of statistics to represent the accuracy of the training and also attempts to ‘draw’ the decision tree that XGB has devised. If we have a quick look in directory ~/xgboost/demo/binary_classification, there should now be a 0002.model file in it ready for deployment with the questionnaire.

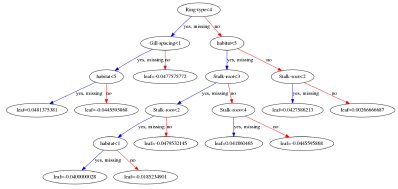

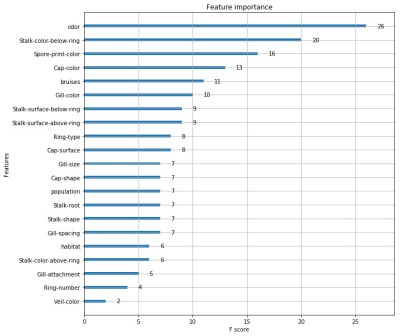

I was interested to explore the decision tree a bit further and look at the way XGB weighted different characteristics of the fungi. I eventually got some rough visualisations working on a Python based Jupyter Notebook script:

Obviously this app is not going to win any Kaggle competitions since the various parameters within the software need to be carefully tuned with the help of all the different software tools available. A good place to start is to tweak the maximum depth of the tree and the number or trees used. Depth = 4 and number = 4 seems to work well for this data. Other parameters include the feature importance type, for example: gain, weight, cover, total_gain or total_cover. These can be tuned using tools such as SHAP.

Finally, this app could easily be adapted to other questionnaire based systems such as diagnosing a particular disease, or deciding whether to buy a particular stock or share in the market place.

An even more basic introduction to ML goes into the baseline theory in a bit more detail – well worth a quick look.

A Lecture By A Fun Guy

Many people hear “fungus” and think of mushrooms. This is akin to hearing “trees” and thinking of apples. Fungus makes up 2% of earth’s total biomass or 10% of the non-plant biomass, and ranges from the deadly to the delicious. This lecture by [Justin Atkin] of [The Thought Emporium] is slightly shorter than a college class period but is like a whole semester’s worth of tidbits, and the lab section is about growing something (potentially) edible rather than a mere demonstration. The video can also be found below the break.

Let’s start with the lab where we learn to grow fungus in a mason jar on purpose for a change. The ingredient list is simple.

- 2 parts vermiculite

- 1 part brown rice flour

- 1 part water

- Spore syringe

Combine, sterilize, cool, inoculate, and wait. We get distracted when cool things are happening so shopping around for these items was definitely hampered by listening to the lecture portion of the video.