No lab in almost any discipline was complete in the 70s and 80s without an X-Y plotter. The height of data acquisition chic, these simple devices were connected to almost anything that produced an analog output worth saving. Digital data acquisition pushed these devices to the curb, but they’re easily found, cheap, and it’s worth a look under the hood to see what made these things tick.

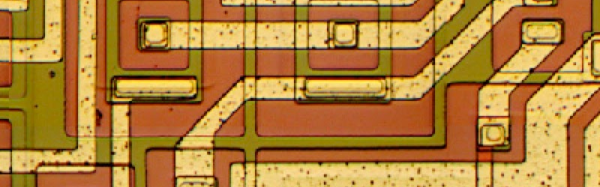

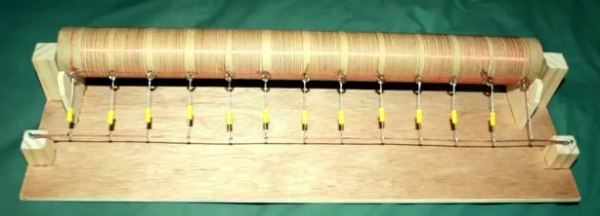

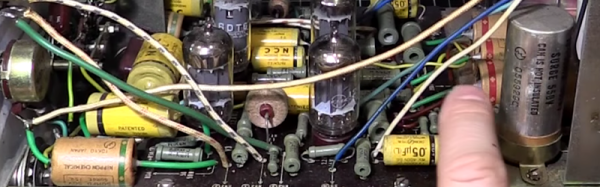

The HP-7044A that [Kerry Wong] scored off eBay is in remarkably good shape four decades after leaving the factory. While the accessory pack that came with it shows its age with dried up pens and disintegrating foam, the plotter betrays itself only by the yellowish cast to its original beige case. Inside, the plotter looks pristine. Completely analog with the only chips being some op-amps in TO-5 cans, everything is in great shape, even the high-voltage power supply used to electrostatically hold the paper to the plotter’s bed. Anyone hoping for at least a re-capping will be disappointed; H-P built things to last back in the day.

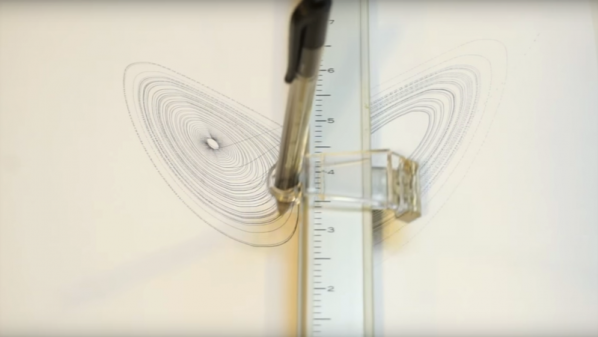

[Kerry] puts the plotter through its paces by programming an Arduino to generate a Lorenz attractor, a set of differential equations with chaotic solutions that’s perfect for an X-Y plotter. The video below shows the mesmerizing butterfly taking shape. Given the plotter’s similarity to an oscilloscope, we wonder if some SDR-based Lissajous patterns might be a fun test as well, or how it would handle musical mushrooms.