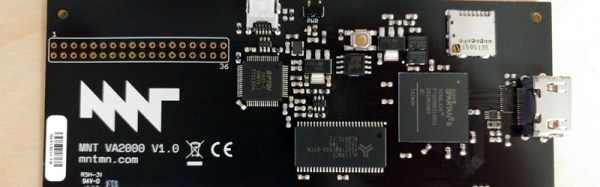

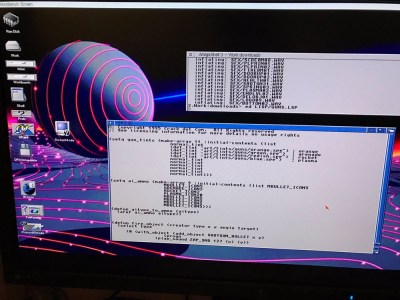

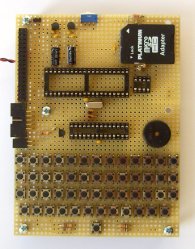

The Apple II was one of the first home computers. Designed by Steve “Woz” Wozniak, it used the MOS technologies 6502 processor, an 8-bit processor running at about 1 MHz. [Maxstaunch] wrote his bachelor thesis about emulating the 6502 in software on an AVR1284 and came up with a handheld prototype Apple II with screen and keyboard.

Originally, [maxstrauch] wanted to build an NES, which uses the same 6502 processor, but he calculated the NES’s Picture Processing Unit would be too complicated for the AVR, so he started on emulating the Apple II instead. It’s not quite there – it can only reference 12K of memory instead of the 64K on the original, so hi-res graphic mode, and therefore, many games, won’t work, but lo-res mode works as well as BASIC (both Integer BASIC and Applesoft BASIC.)

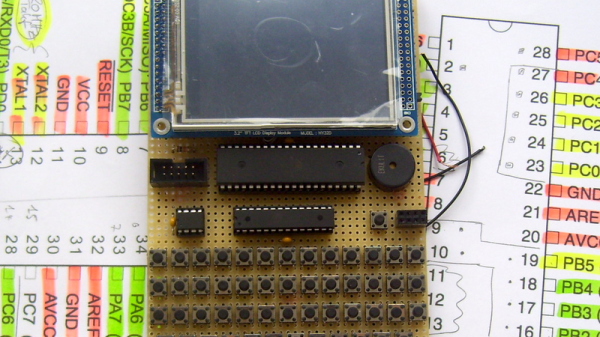

[Maxstrauch] details the 6502 in his thesis and, in a separate document, he gives an overview of the project. A third document has the schematic he used to build his emulator. His thesis goes into great detail about the 6502 and how he maps it to the AVR microcontroller. The build itself is pretty impressive, too. Done on veroboard, the build has a display, keyboard and a small speaker as well as a micro SD card for reading and storing data. For more 6502 projects, check out the Dis-Integrated 6502 and also, this guide to building a homebrew 6502.

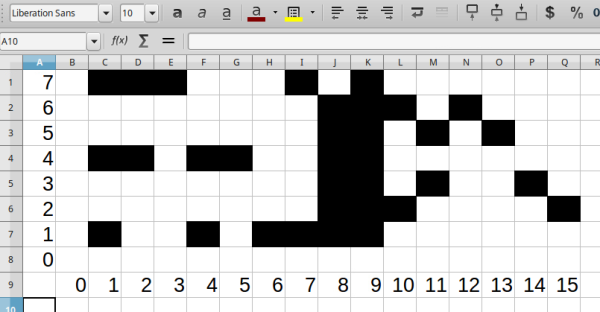

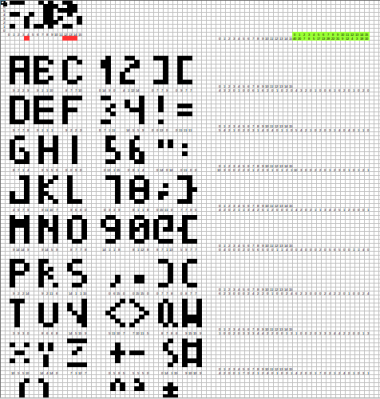

Rather than a pixel-by-pixel representation of the characters, [Jaromir] created a palette of 16 single byte vectors of commonly used patterns. Characters are created by combining these vectors. Each character is 4 x 8 pixels, so 4 vectors are used per character. The hard part was picking commonly used bit patterns for the vectors.

Rather than a pixel-by-pixel representation of the characters, [Jaromir] created a palette of 16 single byte vectors of commonly used patterns. Characters are created by combining these vectors. Each character is 4 x 8 pixels, so 4 vectors are used per character. The hard part was picking commonly used bit patterns for the vectors.