Though as with so many independent inventors the origins of computing can be said to have been arrived at through the work of many people, Alan Turing is certainly one of the foundational figures in computer science. His Turing machine was a thought-experiment computing device in which a program performs operations upon symbols printed on an infinite strip of tape, and can in theory calculate anything that any computer can.

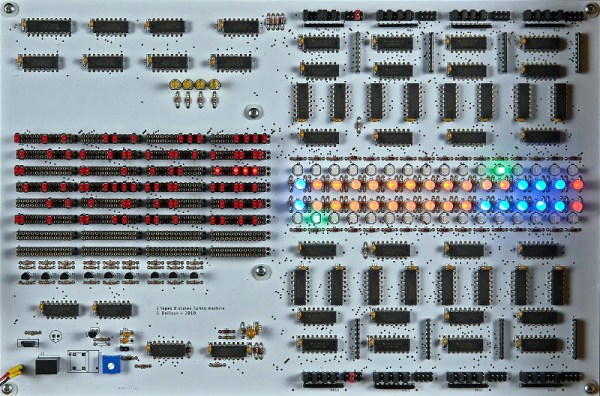

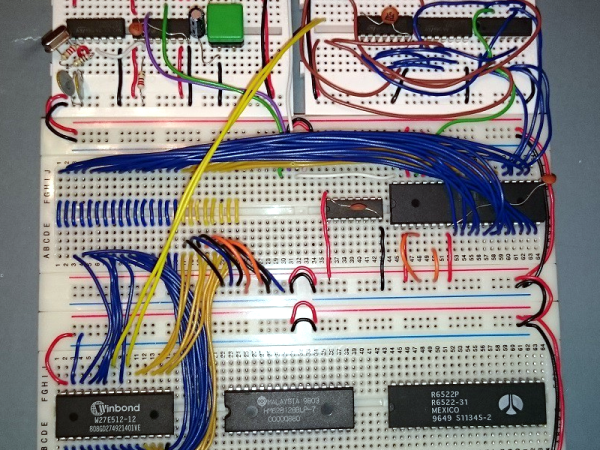

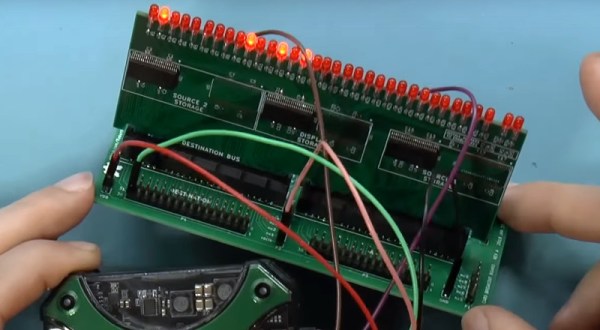

In practice, we do not use Turing machines as our everyday computing platforms. A machine designed as an academic abstract exercise is not designed for efficiency. But that won’t stop Hackaday, and to prove that point [Olivier Bailleux] has done just that using readily available electronic components. His twin-tape Turing machine is presented on a large PCB, and is shown in the video below the break computing the first few numbers of the Fibonacci sequence.

The schematic is available as a PDF, and mostly comprises of 74-series logic chips with the tape contents being displayed as two rows of LEDs. The program is expressed as a pluggable diode matrix, but in a particularly neat manner he has used LEDs instead of traditional diodes, allowing us to see each instruction as it is accessed. The whole is a fascinating item for anyone wishing to learn about Turing machines, though we wish [Olivier] had given us a little more information in his write-up.

That fascination with Turing machines has manifested itself in numerous builds here over the years. Just a small selection are one using 3D printing, another using Lego, and a third using ball bearings. And of course, if you’d like instant gratification, take a look at the one Google put in one of their doodles for Turing’s 100th anniversary.