The Beagle V, a RISC-V-based single board computer from a collaboration between BeagleBoard and Seeed Studios aims to be “The First Affordable RISC-V Computer Designed to Run Linux”. RISC-V is the open-source processor architecture that everyone is interested in because it bypasses proprietary silicon of manufacturers such as Intel or AMD, allowing companies to roll their own silicon processors without licensing fees for the core.

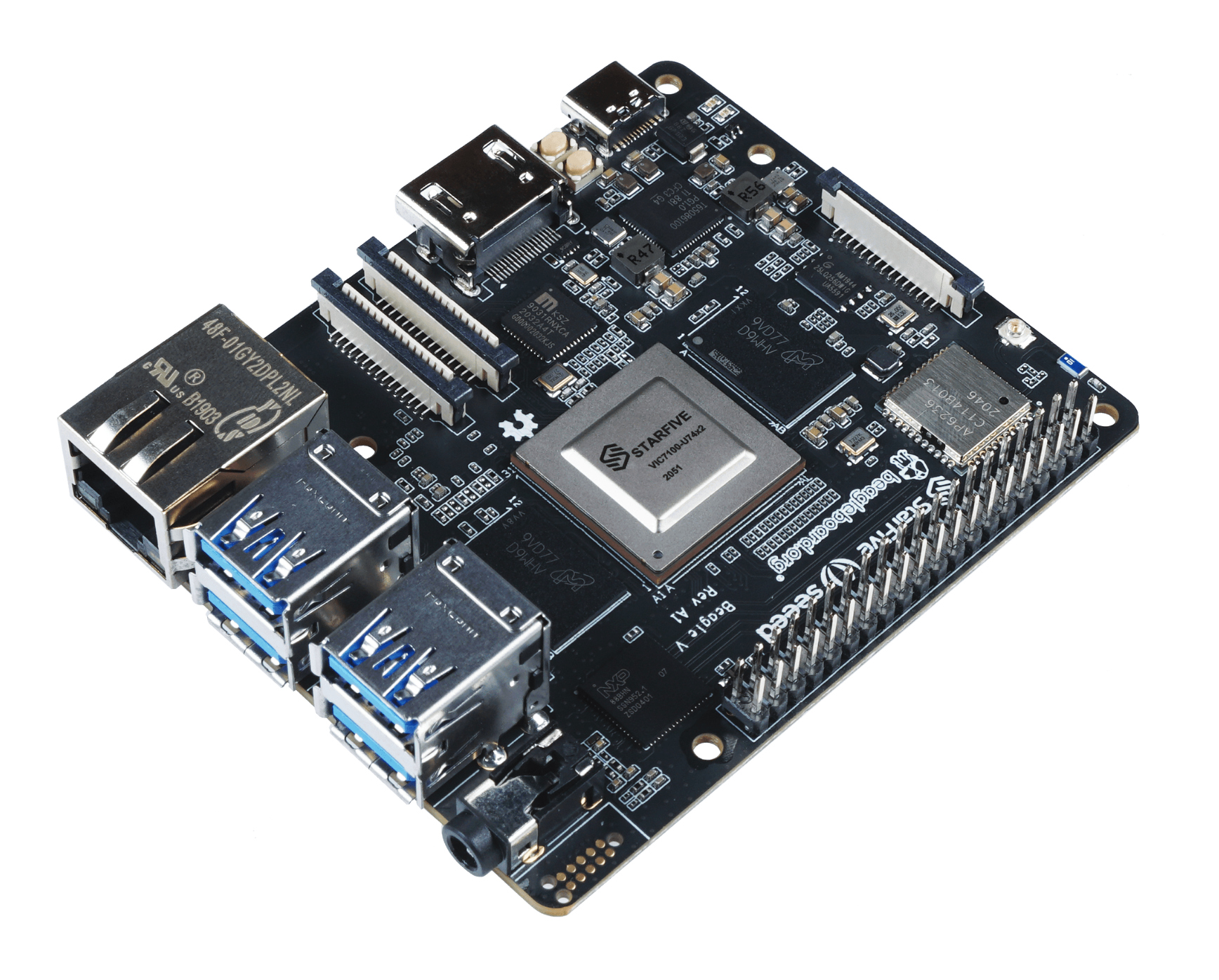

BeagleBoard has long been one of the major players in the Single-Board Computer arena so far dominated by the Raspberry Pi. The board, slightly larger than the company’s previous offerings, features a StarFive dual-core 64-bit RISC-V processor running at a 1.0 GHz clock speed. The spec sheet on their GitHub repo indicates 4 and 8 GB RAM options, built-in WiFi and Bluetooth, and hardware video support for decoding, two camera connectors, one DSI connector for an external display, as well as a full-sized HDMI port. Gigabit Ethernet, four USB-3 ports, an audio jack, and USB-C as the power supply are packed onto the edges of the board. GPIO is routed to a 2×20 pin header.

Seeed Studio pegs the cost of the board at $149 for the 8 GB RAM version, although currently you must apply and be selected to purchase a board in this early stage. It’s unclear if the price will remain unchanged after this first run; the product page notes a coupon code is necessary and the Seeed Studios article indicates this is an introductory price. However, the same article also lists the 4 GB RAM variant at $119. The BeagleBoard page shows a timeline of April 2021 for a “pilot run for community”.

It’s exciting to see RISC-V continue to make inroads. This is a powerful board based around the core, and if successful it will help further prove the viability of open source processing cores in increasingly mainstream products.