The abundance of small networked boards running Linux — like the Raspberry Pi — is a boon for developers. It is easy enough to put a small cheap computer on the network. The fact that Linux has a lot of software is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it is a good bet that anything you want to do has been done. On the other hand, some of the solutions are a bit large for a tiny embedded system.

Take, for example, e-mail. Historically, Linux hosts operate as mail transfer agents that can send and receive mail for all their users and possibly even relay mail to others. In today’s world, that’s usually overkill, but the capability is there. It is possible to install big mail transfer agents into a Raspberry Pi. The question is: should you?

What Do You Want?

The answer, of course, depends on what you want to do. If you have a dedicated board sending out text and maybe even files using an external mail server (like, say, Gmail), then the answer is no. You don’t need a piece of software listening for incoming connections, sorting through multiple users, and so on.

Luckily, there are some simple solutions if you know how to set up and configure them. The key is to avoid the big mail programs that do everything you don’t need.

Mail Front Ends

Let’s tackle sending mail first. If you try to grab the mailutils package, you’ll see it drags along a lot of stuff including mysql. Keep in mind, none of this will actually send mail. It just gives you some tools to get mail ready to send.

Luckily, the bsd-mailx package has a lot less overhead and will do the job. Look at the man page to see what options you have with mailx; you can do things like attach files, set a subject, and specify addresses.

It is a little difficult to set up for Gmail, though, thanks to Google’s security. You’ll need the certutil tool from the libnss3-tools package. You’ll need to create a certificate store, import Google’s certificate, and then set up a lot of options to mailx. I don’t suggest it. If you insist, though, you can find directions on the Web.

SSMTP

By default, programs like mailx and other Linux mail commands rely on a backend (often sendmail). Not only does that drag around too much overhead, it is also a full mail system, sending and receiving and relaying–overkill for our little Pi computers.

Luckily, SSMTP is available which only sends mail and is relatively lightweight. You need a configuration file to point it to your mail server. For Gmail, it would look like this:

#

# Config file for sSMTP sendmail

#

# The person who gets all mail for userids < 1000

# Make this empty to disable rewriting.

root=postmaster

# The place where the mail goes. The actual machine name is required no

# MX records are consulted. Commonly mailhosts are named mail.domain.com

mailhub=smtp.gmail.com:587

# Where will the mail seem to come from?

rewriteDomain=yourdomain.com

# The full hostname

hostname=yourhostname

AuthUser=YourGmailUserID

AuthPass=YourGmailPassword

UseTLS=Yes

UseSTARTTLS=YES

# Are users allowed to set their own From: address?

# YES - Allow the user to specify their own From: address

# NO - Use the system generated From: address

FromLineOverride=YES

You can use a mail agent like mailx or you can just use ssmtp directly:

ssmtp someone@somewhere.com

Enter a message on the standard input and end it with a Control+D (standard end of file for Linux).

Google Authentication

There’s only one catch. If you are using Gmail, you’ll find that Google wants you to use stronger authentication. If you are using two-factor (that is, Google Authenticator), this isn’t going to work at all. You’ll need to generate an app password. Even if you aren’t, you will probably need to relax Google’s fear of spammers on your account. You need to turn on the “Access for less secure apps” setting. If you don’t want to do this on your primary e-mail account, considering making an account that you only use for sending data from the Pi.

Sending Files

Depending on the mail software you use, there are a few ways you can attach a file. However, the mpack program makes it very easy:

mpack -a -s 'Data File' datafile.csv me@hackaday.com

The above command will send datafile.csv as an attachment with the subject “Data File.” Pretty simple.

Receiving Mail

What if you want to reverse the process and receive mail on the Pi? There is a program called fetchmail that can grab e-mails from an IMAP or POP3 server. It is possible to make it only read the first unread message and send it to a script or program of your choosing.

You have to build a configuration file (or use the fetchmailconf program to build it). For example, here’s a simple .fetchmailrc file:

poll imap.gmail.com

protocol IMAP

user "user@gmail.com" with password "yourpassword" mda "/home/pi/mailscript.sh"

folder 'INBOX'

fetchlimit 1

keep

ssl

You can leave the “keep” line out if you don’t mind fetchmail deleting the mail after processing. The file should be in your home directory (unless you specify with the -f option) and it needs to not be readable and writable by other users (e.g., chmod 600 .fetchmailrc). According to the fetchmail FAQ, there are some issues with Gmail, so you might want to consider some of the suggestions provided. However, for simple tasks like this, you should be able to work it all out.

In particular, the mailscript.sh file is where you can process the e-mail. You might, for example, look for certain keyword commands and take some action (perhaps replying using ssmtp).

Special Delivery

You might not think of the Raspberry Pi as an e-mail machine. However, the fact that it is a pretty vanilla Linux setup means you can use all sorts of interesting tools meant for bigger computers. You just have to know they exist.

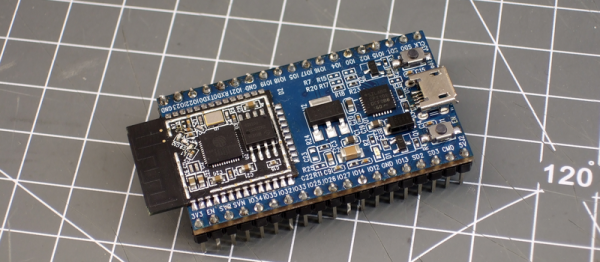

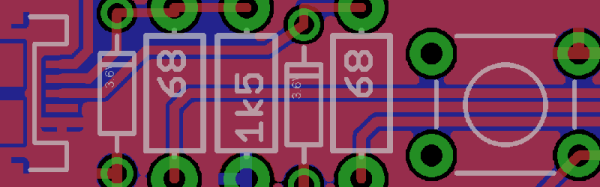

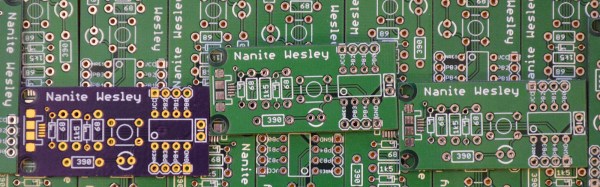

Fritzing came out of the Interaction Design Lab at the University of Applied Sciences of Potsdam in 2007 as a project initiated by Professor Reto Wettach, André Knörig and Zach Eveland. It is frequently compared to Processing, Wiring, or Arduino in that it provides an easy way for artists, creatives, or ‘makers’ to dip their toes into the waters of PCB design.

Fritzing came out of the Interaction Design Lab at the University of Applied Sciences of Potsdam in 2007 as a project initiated by Professor Reto Wettach, André Knörig and Zach Eveland. It is frequently compared to Processing, Wiring, or Arduino in that it provides an easy way for artists, creatives, or ‘makers’ to dip their toes into the waters of PCB design.