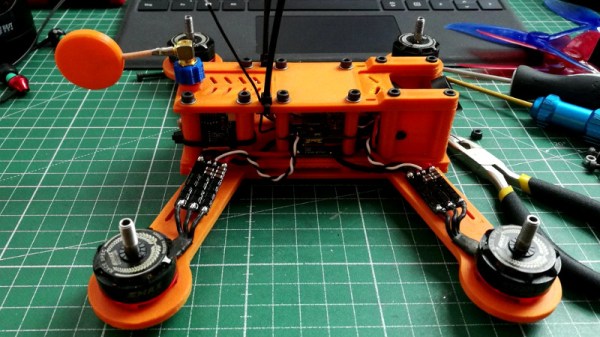

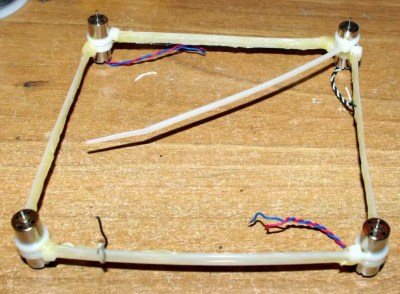

We’ve seen some cheap quadcopter builds over the years, but this one takes the cake. After seeing somebody post a joke about building a quadcopter frame out of zip ties and hot glue, [IronMew] decided to try it for real. The final result is a micro quadcopter that actually flies half-way decently and seems to be fairly resistant to crash damage thanks to the flexible structure.

The first attempts at building the frame failed, as the zip ties (unsurprisingly) were too flexible and couldn’t support the weight of the motors. Eventually, [IronMew] realized that trying to replicate the traditional quadcopter frame design just wasn’t going to work. Rather than a body with arms radiating out to hold the motors, the layout he eventually came up with is essentially the reverse of a normal quadcopter frame.

The first attempts at building the frame failed, as the zip ties (unsurprisingly) were too flexible and couldn’t support the weight of the motors. Eventually, [IronMew] realized that trying to replicate the traditional quadcopter frame design just wasn’t going to work. Rather than a body with arms radiating out to hold the motors, the layout he eventually came up with is essentially the reverse of a normal quadcopter frame.

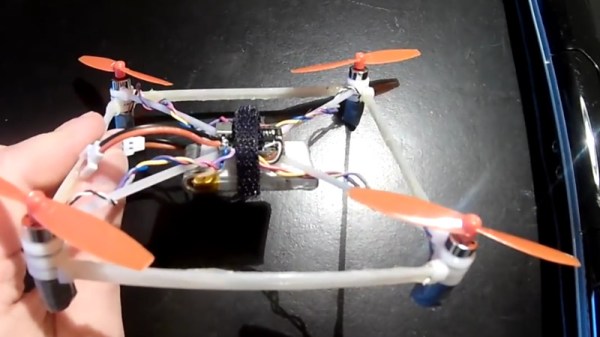

Zip ties reinforced with a healthy coating of hot glue are arranged into a square, with a motor at each corner. Then four zip ties are used to support the central “pod” which holds the battery and electronics. No attempt is made to strengthen this part of the frame, and as such the heavy central pod hangs down a bit in flight. [IronMew] theorizes that this might actually be beneficial in the end, as he believes it could have a stabilizing effect when it comes time to record FPV video.

He mentions that he’s still struggling to get the PID values setup properly in the flight computer, but in the video after the break you can see that it’s flying fairly well for a first attempt. We wouldn’t recommend you tear into a bag of zip ties when it comes time to build your first quadcopter, but it does go to show that there’s plenty of room for experimentation.

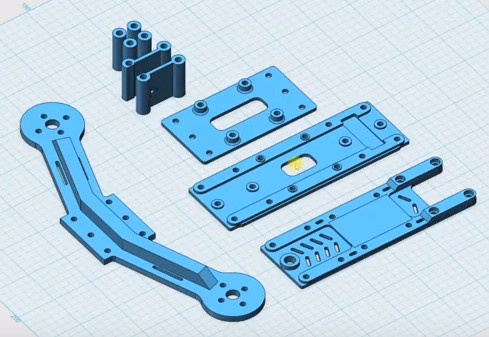

We’ve covered a number of unique quadcopter frames if you’re looking for something to set your next build apart from the rest. If you’ve got a big enough bed you can 3D print a very nice frame, but if you’ve got more time than equipment, you could always cut one out of a piece of plywood.

Continue reading “Zip Tie Quadcopter Frame Is As Cheap As They Come”