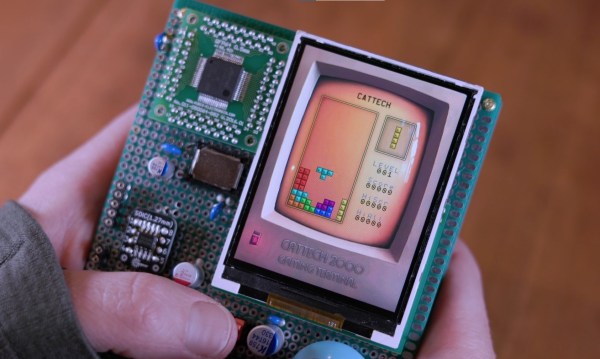

As handheld computing has solidified alongside everything else into the mobile phone, it’s sad that the once promising idea of a general purpose machine in the palm of the hand has taken a turn into the dumbed-down walled-garden offered by smartphone vendors. There was a time when it seemed that a real computer might be a common miniaturized accessory, but while it’s not really come to pass, at least [iketsj] has taken a stab at it. His handheld Hackintosh runs MacOS on a miniature scale, and looks rather nice.

At its heart is the LattePanda Alpha x86 single board computer, with a small custom expansion board for a couple of buttons, a USB hub, a small keyboard, and a display. These parts are all mounted to a baseboard with metal stand-offs, and the power is sourced from a single USB-C socket at the bottom edge. What makes it more extraordinary is that it’s not the first handheld Hackintosh from this maker, the previous one being significantly bigger.

On one hand then, this is home-built PC like any other, assembled from off-the-shelf-parts. But on the other it’s far from normal, for despite its simplicity it forms a very usable small form factor device. The Akruvia Una keyboard uses tactile switches so maybe it’s not the machine to type your thesis on, but other than that it makes a great little machine for MacOS, Linux, or Windows. We like it, and we think you will too when you see the video below the break.