Using a speaker as a microphone is a trick old enough to have become common knowledge, but how often do you see the hack reversed? As part of a larger project to measure the acoustic power of a subwoofer, [DeepSOIC] needed to characterize the phase shift of a microphone, and to do that, he needed a test speaker. A normal speaker’s resonance was throwing off measurements, but an electret microphone worked perfectly.

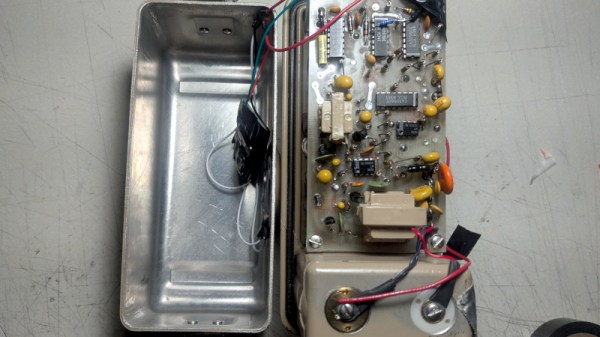

For a test apparatus, [DeepSOIC] had sealed the face of the microphone under test against the membrane of a speaker, and then measured the microphone’s phase shift as the speaker played a range of frequencies. The speaker membrane he started with had several resonance spikes at higher frequencies, however, which made it impossible to take accurate measurements. To shift the resonance to higher frequencies beyond the test range, the membrane needed to be more rigid, and the driver needed to apply force evenly across the membrane, not just in the center. [DeepSOIC] realized that an electret microphone does basically this, but in reverse: it has a thin membrane which can be uniformly attracted and repelled from the electret. After taking a large capsule electret microphone, adding more vent holes behind the diaphragm, and removing the metal mesh from the front, it could play recognizable music.

Replacing the speaker with another microphone gave good test results, with much better frequency stability than the electromagnetic speaker could provide, and let the final project work out (the video below goes over the full project with English subtitles, and the calibration is from minutes 17 to 34). The smooth frequency response of electret microphones also makes them good for high-quality recording, and at least once, we’ve seen someone build his own electrets. Continue reading “2025 Component Abuse Challenge: Playing Audio On A Microphone”