Amazing as volumetric displays are, they have one major drawback: interacting with them is complicated. A 3D mouse is nice, but unless you’ve done a lot of CAD work, it’s a bit unintuitive. Researchers from the Public University of Navarra, however, have developed a touchable volumetric display, bringing touchscreen-like interactions to the third dimension (preprint paper).

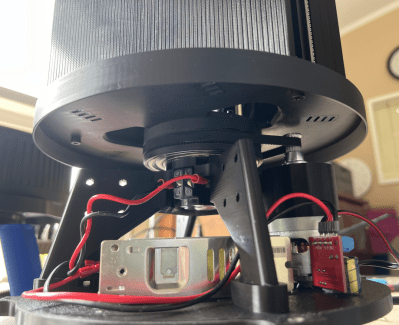

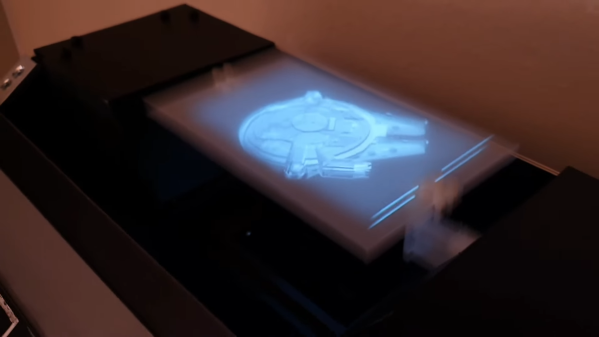

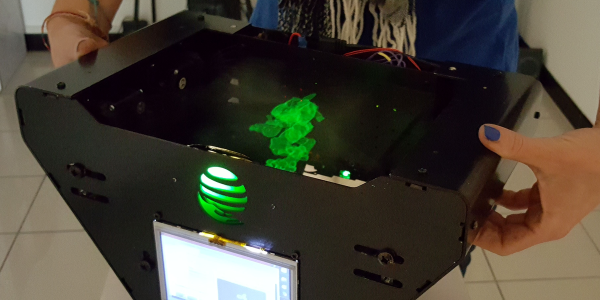

At the core, this is a swept-volume volumetric display: a light-diffusing screen oscillates along one axis, while from below a projector displays cross-sections of the scene in synchrony with the position of the screen. These researchers replaced the normal screen with six strips of elastic material. The finger of someone touching the display deforms one or more of the strips, allowing the touch to be detected, while also not damaging the display.

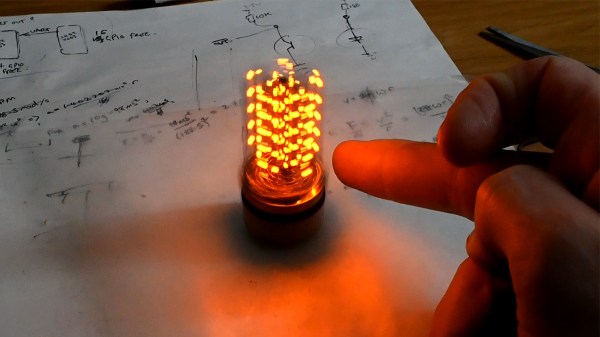

The actual hardware is surprisingly hacker-friendly: for the screen material, the researchers settled on elastic bands intended for clothing, and two modified subwoofers drove the screen’s oscillation. Indeed, some aspects of the design actually cite this Hackaday article. While the citation misattributes the design, we’re glad to see a hacker inspiring professional research.) The most exotic component is a very high-speed projector (on the order of 3,000 fps), but the previously-cited project deals with this by hacking a DLP projector, as does another project (also cited in this paper as source 24) which we’ve covered.

While interacting with the display does introduce some optical distortions, we think the video below speaks for itself. If you’re interested in other volumetric displays, check out this project, which displays images with a levitating styrofoam bead.

Continue reading “Elastic Bands Enable Touchable Volumetric Display”