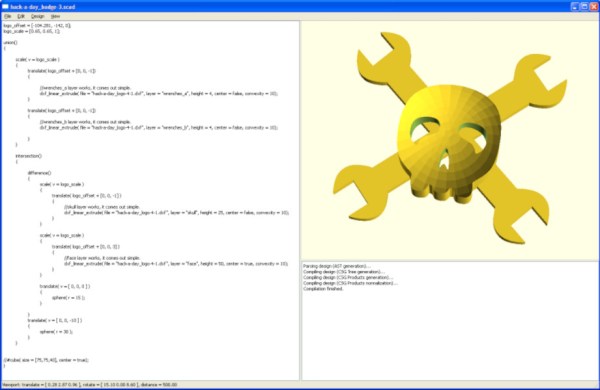

OpenSCAD is a fantastic free tool for 3D modeling, but it’s far less intuitive to use for non-programmers than mouse-driven programs such as Tinkercad. Powerful as it may be, the learning curve is pretty steep. OpenSCAD’s own clickable cheat sheet and manual comes in handy all the time, but those are really more of a reference than anything else. Never fear, because [Jochen Kerdels] had quite the productive lockdown and wrote a free comprehensive guide to mastering OpenSCAD.

[Jochen]’s book opens with a nice introduction to OpenSCAD and it’s user environment and quickly moves into 10 useful projects of increasing complexity that start with simple stuff like wall anchors and shelf brackets and ends with recursive trees.

[Jochen]’s book opens with a nice introduction to OpenSCAD and it’s user environment and quickly moves into 10 useful projects of increasing complexity that start with simple stuff like wall anchors and shelf brackets and ends with recursive trees.

There are plenty of printing tips along the way to help realize these projects with minimum frustration, and the book wraps up by covering extra functions not expressly used in the projects.

Of course, you could always support [Jochen]’s Herculean effort by buying the print edition and forcing yourself to type everything in instead of copy/pasting, or give it to someone to introduce them to all the program has to offer.

Need help mastering OpenSCAD workflow? We’ve got that. Just want to make some boxes or airfoils? We have those in stock, too.

Main and thumbnail images via [Devlin Thyne]