The average FDM 3D printer is not so different from your garden variety laser cutter. They’re often both Cartesian-coordinate based machines, but with different numbers of axes and mounting different tools. As [Gosse Adema] shows, turning a 3D printer into a laser cutter can actually be a remarkably easy job.

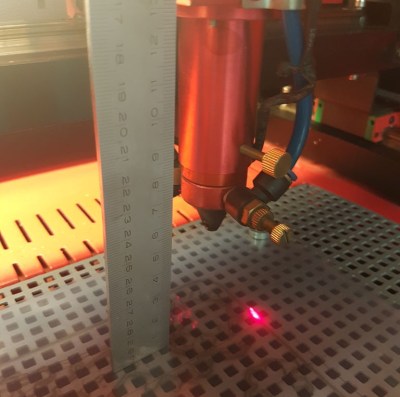

The build starts with an Anet A8 3D printer. It’s an affordable model at the lower end of the FDM printer market, making it accessible to a broad range of makers. With the help of some 3D printed brackets, it’s possible to replace the extruder assembly with a laser instead, allowing the device to cut and engrave various materials.

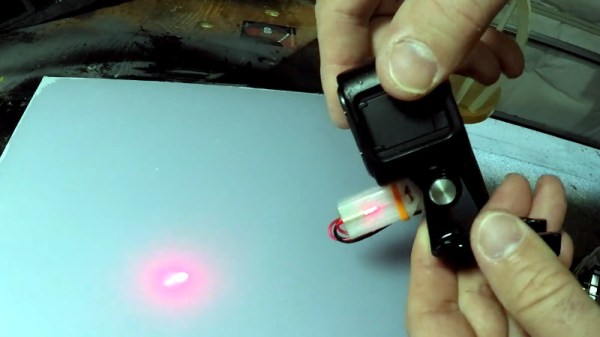

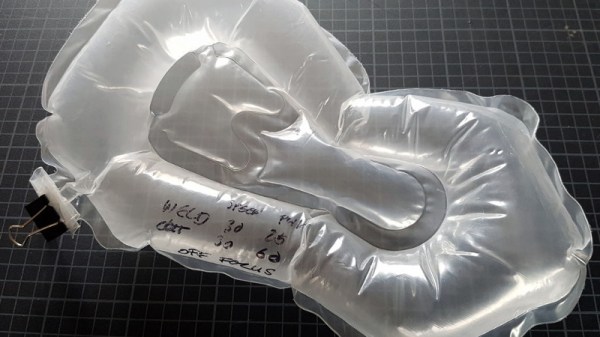

[Gosse] went with a 5500 mW diode laser, which allows for the cutting and engraving of wood, some plastics and even fabrics. Unlike a dedicated laser cutter there are no safety interlocks and no enclosure, so it’s important to wear goggles when the device is operating. Some tinkering with G-Code is required to get things up and running, but it’s a small price to pay to get a laser cutter on your workbench.

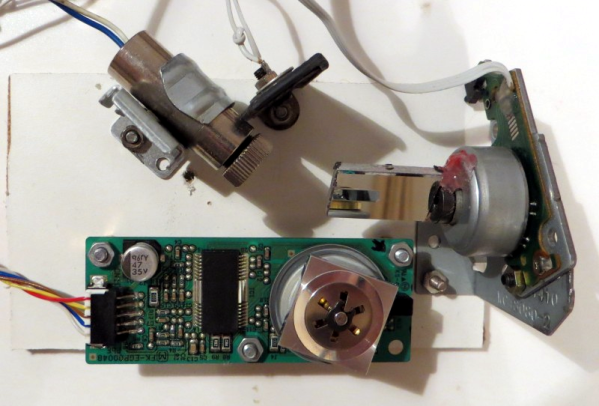

We’ve seen [Gosse]’s 3D printer experiments before, with the Anet A8 serving well as a PCB milling machine.