It might not be obvious unless you’ve taken one apart, but most of the TVs and monitors listed as “LED” are simply LCD panels that use a bank of LEDs to illuminate them from behind. Similarly, what are generally referred to as “LCDs” are LCD panels that use fluorescent tubes for illumination. To get a true LED display with no separate backlight, you need OLED. Confused? Welcome to the world of consumer technology.

With those distinctions in mind, the hack that [Zenodilodon] recently performed on a broken “LED TV” is really rather brilliant. By removing the dead white LED backlights and replacing them with RGB LED strips, he not only got the TV working again, but also imbued it with color changing abilities. Perfect for displaying music visualizations, or kicking your next film night into high gear with a really trippy showing of Seven Samurai.

With those distinctions in mind, the hack that [Zenodilodon] recently performed on a broken “LED TV” is really rather brilliant. By removing the dead white LED backlights and replacing them with RGB LED strips, he not only got the TV working again, but also imbued it with color changing abilities. Perfect for displaying music visualizations, or kicking your next film night into high gear with a really trippy showing of Seven Samurai.

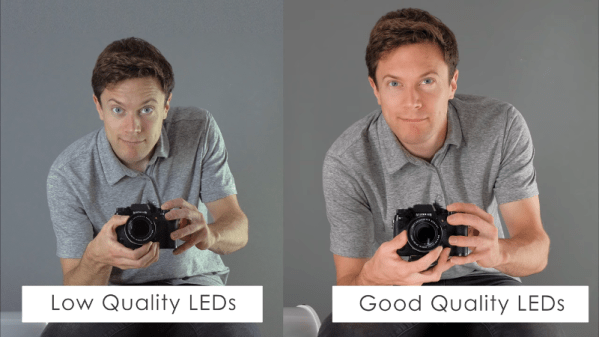

In the video after the break, [Zenodilodon] starts his RGB transplant by stripping the TV down to its principal parts. The original LEDs were toasted, so they might as well go straight in the bin alongside their driver electronics. But the LCD panel itself was working fine (tested by shining a laser pointer through it to see if there was an image), and the plastic sheets which diffuse the LED backlight were easily salvaged.

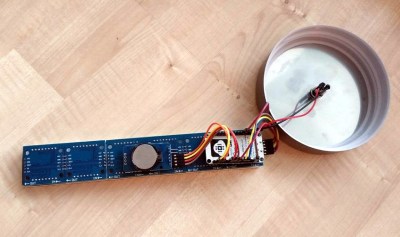

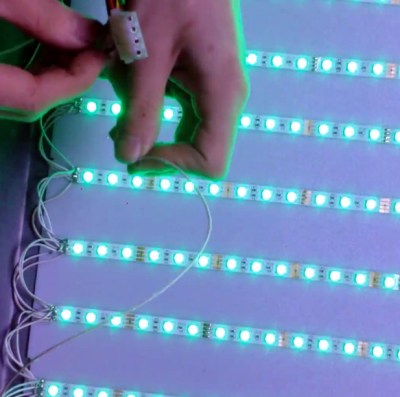

With the old LEDs removed, [Zenodilodon] laid out his new strips and soldered them up to the external controller. He was careful to use all white wires, as he was worried colored wires might reflect the white light and be noticeable on the display. After buttoning the TV back up, he went through a few demonstrations to show how the image looked with the white LEDs on, as well as some interesting effects that could be seen when the LEDs are cycling through colors.

The RGB strips don’t light up the display as well as the original backlight did, as there are some obvious dark spots and you can see some horizontal lines where the strips are. But [Zenodilodon] says the effect isn’t too bad in real-life, and considering it was a cheap TV the image quality was probably never that great to begin with.

On the flip side, if you find an LED TV or monitor in the trash with a cracked screen, it might be worth taking it home to salvage its super-bright white LEDs for your lighting projects.

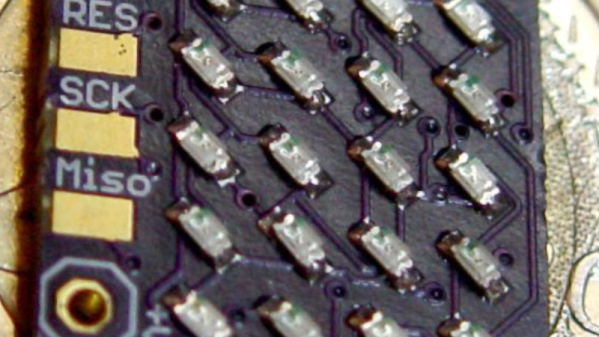

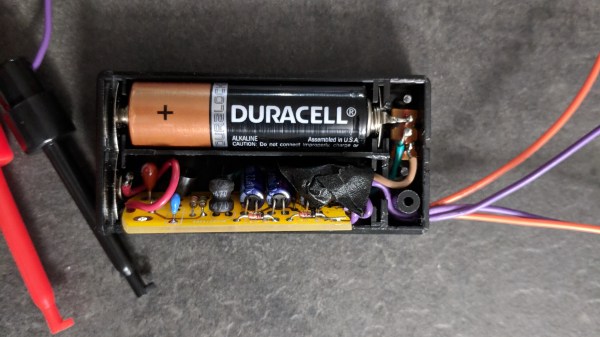

The device’s low current means that nixie and neon elements won’t light up very brightly, but they will light up enough to verify function and operation. [The LED Artist] reports that touching the output terminals of the generator only causes a slight tingling sensation.

The device’s low current means that nixie and neon elements won’t light up very brightly, but they will light up enough to verify function and operation. [The LED Artist] reports that touching the output terminals of the generator only causes a slight tingling sensation.