Working on a project into the wee hours is hardly uncommon for us hackers, but if you’re consistently sleeping until the afternoon, it’s possible you’re suffering from a condition known as Delayed Phase Sleep Disorder (DPSD). Put simply, your body’s internal clock is out of alignment with the world around you. One of the ways to treat this condition is to expose yourself to bright light in the morning, which can help you wake up and feel more refreshed. Unfortunately, these so-called “Bright Light Therapy” boxes tend to be pretty expensive.

Looking for a way to treat his own DPSD, [Edward Shin] decided to build his own light box based on the research he’d done on the various commercial offerings out there. After all, a box full of bright lights that operates on a timer doesn’t seem particularly complex. Of course, in reality there’s a bit more to it than that, but so far the results are certainly promising.

Looking for a way to treat his own DPSD, [Edward Shin] decided to build his own light box based on the research he’d done on the various commercial offerings out there. After all, a box full of bright lights that operates on a timer doesn’t seem particularly complex. Of course, in reality there’s a bit more to it than that, but so far the results are certainly promising.

The first decision [Edward] had to make was what kind of light he wanted. Classic light therapy devices, often used to treat Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD), tend to be full spectrum lights that try and simulate sunlight. But in his research, he found a paper from Nature that explained the melanopsin in the human eye responds primarily to blue and green light. But as intense blue light can apparently lead to macular degeneration, he decided to go with green.

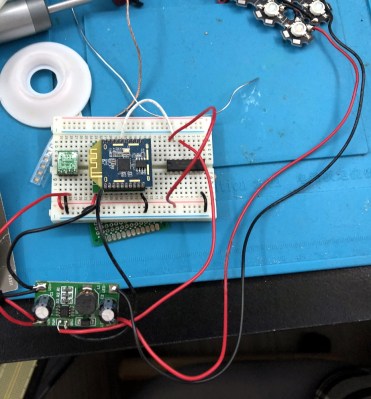

Since [Edward] already uses the Philips Hue system for his home’s lighting, he wanted to bring his therapy light into that ecosystem. The idea was that he could easily schedule his new green light box to go on when he wanted to wake up in the morning. So he used the Mesh Bee from Seeed Studio which not only supports ZigBee, but for which software is available to emulate a Hue bulb. Then he just needed to pair that with a sufficiently beefy LED driver and some 510 nm emitters. Everything is enclosed in a box made of laser cut wood that’s designed to hang from the headboard and shine down onto his face.

Over the years we’ve seen a number of similar projects trying to address SAD, so the idea of a hacker tweaking the concept to tackle DPSD seems a natural enough evolution of the idea. Just remember to speak with a medical professional before coming up with a homebrew treatment plan.