While for some of us it’s a distant memory, every serious electronics hobbyist must at some point make the leap from working with through-hole components to Surface Mount Devices (SMD). At first glance, the diminutive components can be quite intimidating — how can you possibly work with parts that are literally smaller than a grain of rice? But of course, like anything else, with practice comes proficiency.

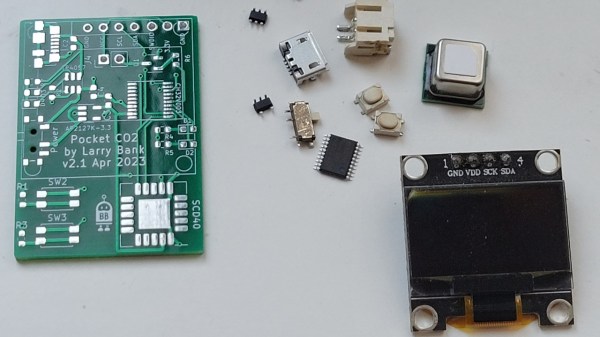

It’s at this silicon precipice that [Larry Bank] recently found himself. While better known on these pages for his software exploits, he recently decided to add SMD electronics to his repertoire by designing and assembling a pocket-sized CO2 monitor. While the monitor itself is a neat gadget that would be worthy of these pages on its own, what’s really compelling about this write-up is how it documents the journey from SMD skeptic to convert in a very personal way.

At first, [Larry] admits to being put off by projects using SMD parts, assuming (not unreasonably) that it would require a significant investment in time and money. But eventually he realized that he could start small and work his way up; for less than $100 USD he was able to pick up both a hot air rework station and a hotplate, which is more than enough to get started with a wide range of SMD components. He experimented with using solder stencils, but even there, ultimately found them to be an unnecessary expense for many projects.

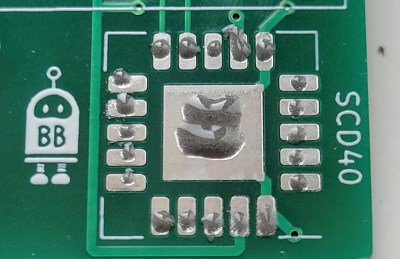

While the bulk of the page details the process of assembling the board, [Larry] does provide some technical details on the device itself. It’s powered by the incredibly cheap CH32V003 microcontroller — they cost him less than twenty cents each for fifty of the things — paired with the ubiquitous 128×64 SSD1306 OLED, TP4057 charge controller, and a SCD40 CO2 sensor.

Whether you want to build your own portable CO2 sensor (which judging from the video below, is quite nice), or you’re just looking for some tips on how to leave those through-hole parts in the past, [Larry] has you covered. We’re particularly eager to see more of his work with the CH32V003, which is quickly becoming a must-have in the modern hardware hacker’s arsenal.

Continue reading “Pocket CO2 Sensor Doubles As SMD Proving Ground”