Isaac Asimov described the business of rocket fuel research as “playing footsie with liquids from Hell.” If that piques your interest even a little, even if you do nothing else today, read the first few pages of IGNITION! which is available online for free. I bet you won’t want to stop reading.

IGNITION! An Informal History of Liquid Rocket Propellants is about how modern liquid rocket fuel came to be. Written by John D. Clark and published in 1972, the title might at first glance make the book sound terribly dry — it’s not. Liquid rocket fuel made modern rocketry possible. But most of us have no involvement with it at all besides an awareness that it exists, and that makes it easy to take for granted.

Most of us lack any understanding of the fact that its development was the result of a whole lot of hard scientific work, and that work required brilliance (and bravery) and had many frustrating dead ends. It was also an amazingly dangerous business to be in. Isaac Asimov put it this way in the introduction:

“[A]nyone working with rocket fuels is outstandingly mad. I don’t mean garden-variety crazy or a merely raving lunatic. I mean a record-shattering exponent of far-out insanity.

There are, after all, some chemicals that explode shatteringly, some that flame ravenously, some that corrode hellishly, some that poison sneakily, and some that stink stenchily. As far as I know, though, only liquid rocket fuels have all these delightful properties combined into one delectable whole.”

At the time that the book was written and published, most of the work on liquid rocket fuels had been done in the 40’s, 50’s, and first half of the 60’s. There was plenty written about rocketry, but very little about the propellants themselves, and nothing at all written about why these specific substances and not something else were being used. John Clark — having run a laboratory doing propellant research for seventeen years — had a unique perspective of the whole business and took the time to write IGNITION! An Informal History of Liquid Rocket Propellants.

Liquid rocket propellant was in two parts: a fuel and an oxidizer. The combination is hypergolic; that is, the two spontaneously ignite and burn upon contact with each other. As an example of the kinds of details that mattered (i.e. all of them), the combustion process had to be rapid and complete. If the two liquids flow into the combustion chamber and ignite immediately, that’s good. If they form a small puddle and then ignite, that’s bad. There are myriad other considerations as well; the fuel must burn at a manageable temperature (so as not to destroy the motor), the energy density of the fuel must be high enough to be a practical fuel in the first place, and so on.

Liquid rocket propellant was in two parts: a fuel and an oxidizer. The combination is hypergolic; that is, the two spontaneously ignite and burn upon contact with each other. As an example of the kinds of details that mattered (i.e. all of them), the combustion process had to be rapid and complete. If the two liquids flow into the combustion chamber and ignite immediately, that’s good. If they form a small puddle and then ignite, that’s bad. There are myriad other considerations as well; the fuel must burn at a manageable temperature (so as not to destroy the motor), the energy density of the fuel must be high enough to be a practical fuel in the first place, and so on.

The actual process of discovering exactly what materials to use and how precisely to make them work in a rocket motor was the very essence of the phrase “the devil is in the details.” For every potential solution, there was a mountain of dead-end possibilities that tantalizingly, infuriatingly, almost worked.

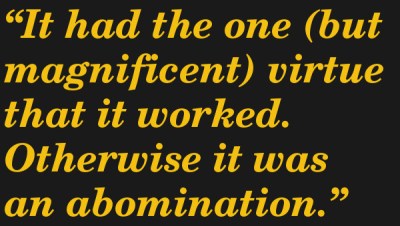

The first reliable, workable propellant combination was Aniline and Red Fuming Nitric Acid (RFNA). “It had the one – but magnificent – virtue that it worked,” writes Clark. “Otherwise it was an abomination.” Aniline was difficult to procure, ferociously poisonous and rapidly absorbed through skin, and froze at an inconvenient -6.2 Celsius which limited it to warm weather only. RFNA was fantastically corrosive, and this alone went on to cause no end of problems. It couldn’t be left sitting in a rocket tank waiting to be used for too long, because after a while you wouldn’t have a tank left. It needed to be periodically vented while in storage. Pouring it gave off dense clouds of remarkably toxic gas. This propellant would go on to cause incredibly costly and dangerous problems, but it worked. Still, no one wanted to put up with any of it one moment longer than they absolutely had to. As a result, that combination was not much more than a first step in the whole process; there was plenty of work left to do.

By the mid-sixties, liquid rocket propellant was a solved problem and the propellant community had pretty much worked themselves out of a job. Happily, a result of that work was this book; it captures history and detail that otherwise would simply have disappeared.

Clark has a gift for writing, and the book is easy to read and full of amusing (and eye-widening) anecdotes. Clark doesn’t skimp on the scientific background, but always in an accessible way. It’s interesting, it’s relevant, it’s relatable, and there is plenty to learn about how hard scientific and engineering development actually gets done. Download the PDF onto your favorite device. You’ll find it well worth the handful of evenings it takes to read through it.

Liquid rocket propellant was in two parts: a fuel and an oxidizer. The combination is hypergolic; that is, the two spontaneously ignite and burn upon contact with each other. As an example of the kinds of details that mattered (i.e. all of them), the combustion process had to be rapid and complete. If the two liquids flow into the combustion chamber and ignite immediately, that’s good. If they form a small puddle and then ignite, that’s bad. There are myriad other considerations as well; the fuel must burn at a manageable temperature (so as not to destroy the motor), the energy density of the fuel must be high enough to be a practical fuel in the first place, and so on.

Liquid rocket propellant was in two parts: a fuel and an oxidizer. The combination is hypergolic; that is, the two spontaneously ignite and burn upon contact with each other. As an example of the kinds of details that mattered (i.e. all of them), the combustion process had to be rapid and complete. If the two liquids flow into the combustion chamber and ignite immediately, that’s good. If they form a small puddle and then ignite, that’s bad. There are myriad other considerations as well; the fuel must burn at a manageable temperature (so as not to destroy the motor), the energy density of the fuel must be high enough to be a practical fuel in the first place, and so on.