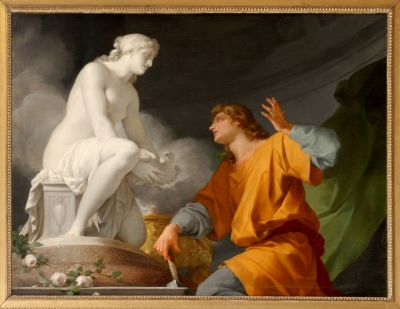

The concept of artificial intelligence dates back far before the advent of modern computers — even as far back as Greek mythology. Hephaestus, the Greek god of craftsmen and blacksmiths, was believed to have created automatons to work for him. Another mythological figure, Pygmalion, carved a statue of a beautiful woman from ivory, who he proceeded to fall in love with. Aphrodite then imbued the statue with life as a gift to Pygmalion, who then married the now living woman.

Throughout history, myths and legends of artificial beings that were given intelligence were common. These varied from having simple supernatural origins (such as the Greek myths), to more scientifically-reasoned methods as the idea of alchemy increased in popularity. In fiction, particularly science fiction, artificial intelligence became more and more common beginning in the 19th century.

But, it wasn’t until mathematics, philosophy, and the scientific method advanced enough in the 19th and 20th centuries that artificial intelligence was taken seriously as an actual possibility. It was during this time that mathematicians such as George Boole, Bertrand Russel, and Alfred North Whitehead began presenting theories formalizing logical reasoning. With the development of digital computers in the second half of the 20th century, these concepts were put into practice, and AI research began in earnest.

Over the last 50 years, interest in AI development has waxed and waned with public interest and the successes and failures of the industry. Predictions made by researchers in the field, and by science fiction visionaries, have often fallen short of reality. Generally, this can be chalked up to computing limitations. But, a deeper problem of the understanding of what intelligence actually is has been a source a tremendous debate.

Despite these setbacks, AI research and development has continued. Currently, this research is being conducted by technology corporations who see the economic potential in such advancements, and by academics working at universities around the world. Where does that research currently stand, and what might we expect to see in the future? To answer that, we’ll first need to attempt to define what exactly constitutes artificial intelligence.