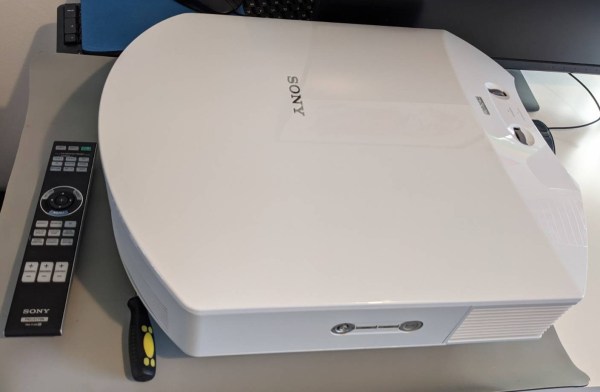

When you’re the proud owner of a beast of a projector like the Sony HW65ES (£2800 in 2016), you are understandably upset when it stops working. In the case of [Wettergren] it appears that a lightning strike in the Summer of 2021 managed to take out the HDMI inputs, with no analog or other input options remaining. Although a new board with the HDMI section would cost 500 €, it couldn’t be purchased separately, and a repair shop quoted 1800 € to repair it, which would be a raw deal. So, left with the e-waste or DIY repair options, [Wettergren] chose the latter.

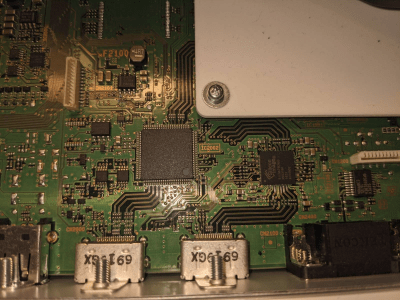

Suffice it to say that taking one of these large projectors apart is rather an adventure, as is extracting the input PCB. On this board some probing showed that while the HDMI 2 port showed some signs of life, with its DDC lines functioning and the EDID readable. The HDMI 1 port had a dead short on these lines, which got traced back to a dead Sil9589CTUC IC, while HDMI was connected to the Sil9679 IC next to it. With this easy part done, the trick was finding replacements for what is decidedly not an off-the-shelf component, but fortunately EBay came through. This just left the slow agony of microsoldering to replace the dead IC, which ultimately succeeded.

After the second repair attempt in May of 2022, the projector is still working in December of 2023, proving that a bit of persistence, a bit of EBay luck and a microsoldering bench with the skills to use it can bring many devices back from the brink to give them a happy second life.

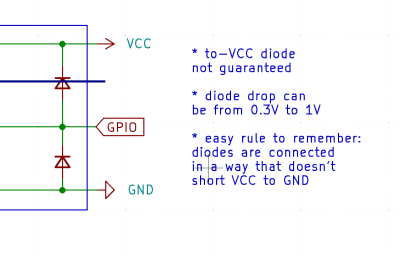

Thankfully, in modern-day Western climates and with modern tech, you are not likely to encounter ESD-caused problems, but they were way more prominent back in the day. For instance, older hackers will have stories of how FETs were more sensitive, and touching the gate pin mindlessly could kill the FET you’re working with. Now, we’ve fixed this problem, in large part because we have added ESD-protective diodes inside the active components most affected.

Thankfully, in modern-day Western climates and with modern tech, you are not likely to encounter ESD-caused problems, but they were way more prominent back in the day. For instance, older hackers will have stories of how FETs were more sensitive, and touching the gate pin mindlessly could kill the FET you’re working with. Now, we’ve fixed this problem, in large part because we have added ESD-protective diodes inside the active components most affected.