[Joshua Elsdon] and [Thomas Branch] needed a educational hardware platform that would fit into the constrained spaces and budgets of college classes. Because nothing out there that was cheap, simple and capable enough to fit their program, the two teachers for robotics at the Imperial College Robotics Society set out to build their own – and entered the Hackaday Prize with a legion of open source Micro Robots.

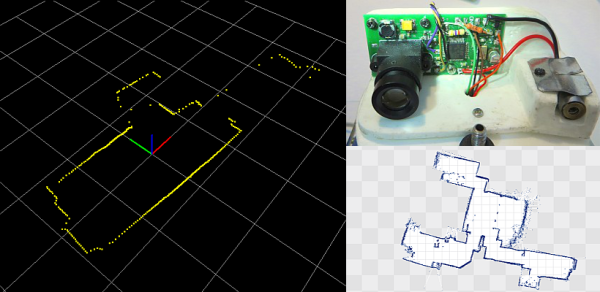

These small robots have a base area of 2 cm2 and a price tag of about £10 (about $14) each, once they are produced in quantities. They feature two onboard stepper motors, an RGB-LED, battery, a line-following sensor, collision-sensors and a bidirectional infrared transmitter for communicating with a master system, the ‘god bot’. The master system is based on a Raspberry Pi with little additional hardware. It multiplexes the IR-communication with all the little robots and simultaneously tracks their position and orientation through a camera, identifying them via their colored onboard LED. The master system also provides a programming interface for the robots, so that no firmware flashing procedure is required for students to get their code running. This is a well-designed, low-cost multi-robot system, and with onboard sensors, stepper motor odometry, and absolute positioning feedback, these little robots can be taught quite a few tricks.

Building tiny robots comes with a lot of regular-sized challenges, and we’re delighted to follow [Joshua Elsdon] and [Thomas Branch] on their journey from assembling the tiny PCBs over experimenting with 3D printing and casting techniques to produce the tiny wheels to the ROS programming. The diligent duo is present in the Hackaday prize twice: With their own Micro Robots project and with their contribution to the previously covered ODrive – an open source BLDC servo controller. We are already curious about their next feat! The below video shows a successful test of the camera feedback integration into the ROS.