Decades ago, shows like Star Trek, The Jetsons, and Lost in Space promised us a future full of helpful computers and robot assistants. Unfortunately, we haven’t quite gotten our general-purpose helper to do all of our tasks with a simple voice command yet. But if some sweat equity is applied, we can get machines to do specific tasks for us under some situations. [Max Maker] built this remote-controlled lawnmower which at least minimizes the physical labor he needs to do to cut his grass.

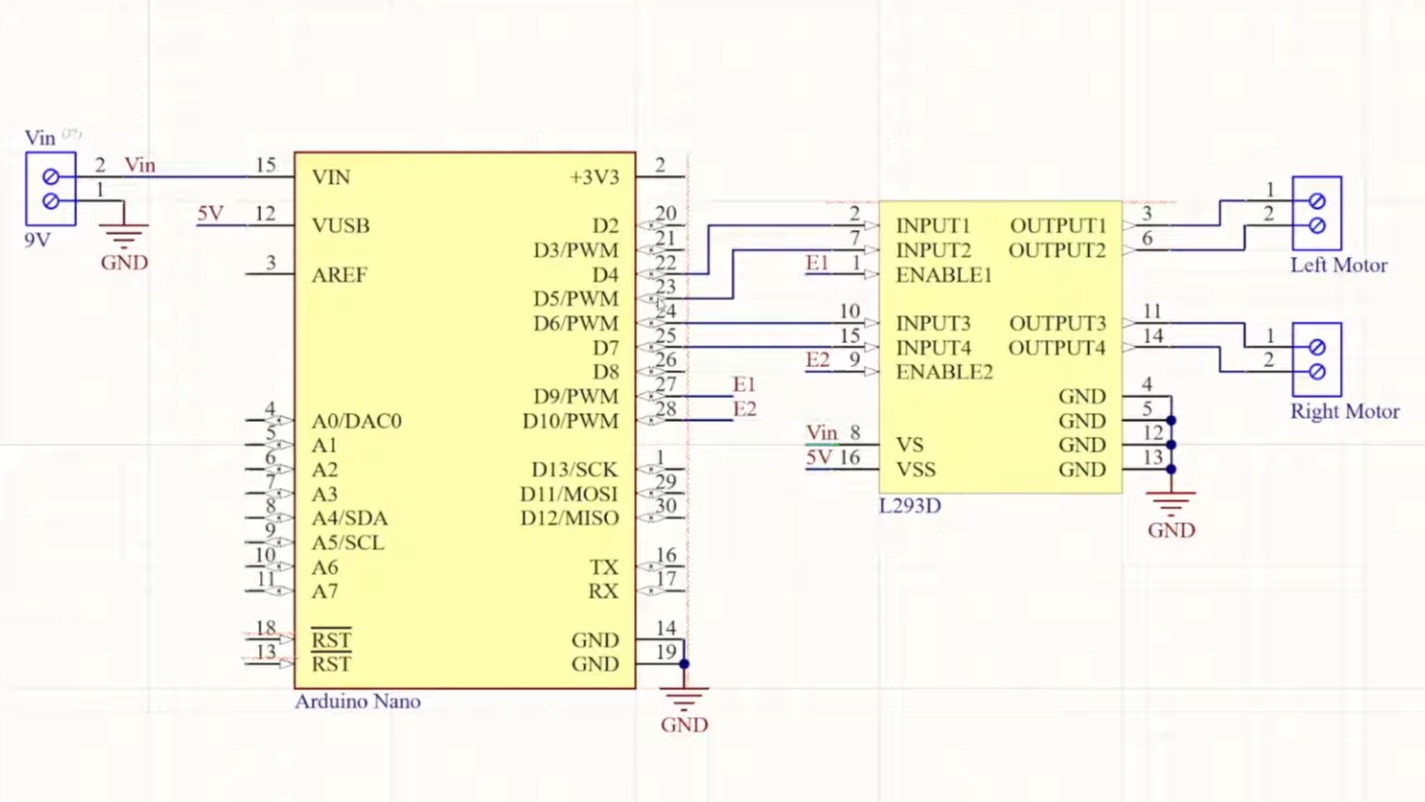

The first step in the project was to remove the human interface parts of the push mower and start working on a frame for the various control mechanisms. This includes adding an actuator to raise and lower the mower deck on the fly. Driving the new rear wheels are two wheelchair motors, which allow it to use differential steering, with a set of casters up front for maximum maneuverability. An Arduino Mega sits in a custom enclosure to control everything and receive the RC signals, alongside the mower’s batteries and the motor controllers for the drive wheels.

After some issues with programming, [Max] has an effective remote controlled mower that he can use to mulch leaves or cut grass without getting out of his chair. It would also make an excellent platform if he decides to fully automate it in the future, which is a project that has been done fairly effectively in the past even at much larger scales.