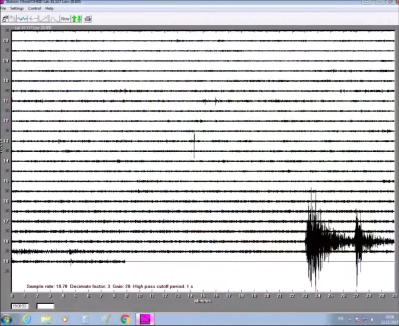

If you’re a child, there are certain things you’re taught even though they’re probably not directly relevant to your life. We teach young kids all about dinosaurs, and we teach older kids all about how the mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell. We also teach kids about natural phenomena like earthquakes, and the equipment used to measure them. Namely, seismometers. You might like to satisfy your own child-like curiosity by building one of your own, like [mircemk] did.

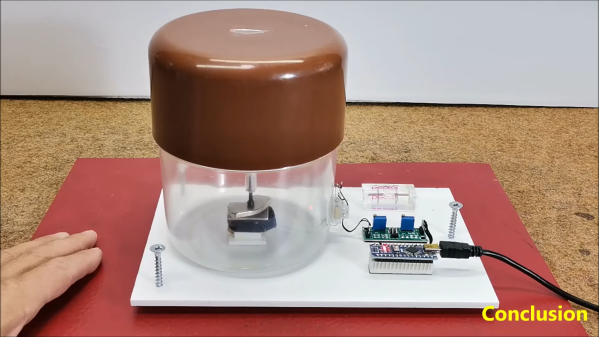

The build starts with a sensitive geophone of [mircemk’s] own design. That’s basically a microphone but it’s for picking up vibrations in the ground, not in the air. However, a geophone is not enough. You need to be able to pick up the signals from the geophone and then plot them if you want a seismometer.

First, the signals from the geophone must be amplified, which is achieved with a small circuit based around the LM358 op-amp. From there, the signal is sent to an Arduino where the output is captured via the analog-to-digital converter. This passes the signal to an attached PC which plots the results using a piece of software called NERdaq, which was developed for schools that built their own slinky-based seismometers.

[mircemk] reports that this setup has served as a reliable tool for visualizing earthquake activity for over 6 years. Though, it bears noting, it’s not calibrated so don’t expect to get science grade results out of it. Regardless, though, it’s a super cool way to understand more about what is going on with the geology around us. Video after the break.

Continue reading “A Simple Seismometer You Can Build Yourself”