Attempts to make a viable nuclear fusion reactor have on the whole been the domain of megabucks projects supported by countries or groups of countries, such as the European JET or newer ITER projects. This is not to say that smaller efforts aren’t capable of making their own advances, operations in both the USA and the UK are working on new reactors that use a novel superconducting tape to achieve a much smaller device.

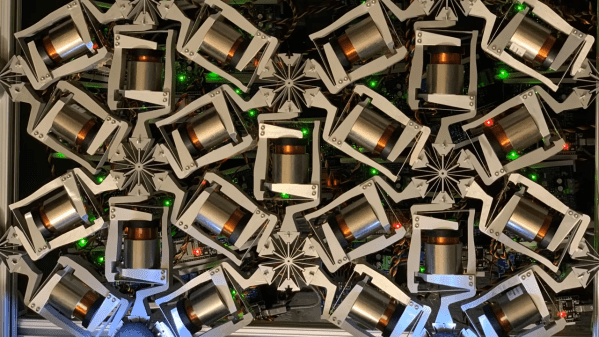

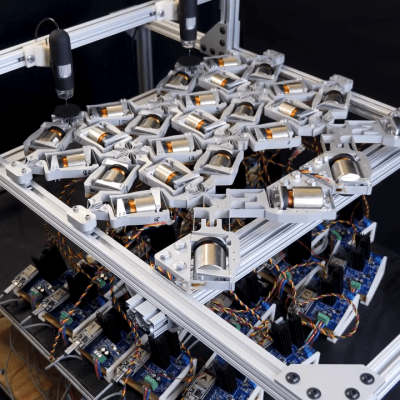

The reactors in the works from both Oxfordshire-based Tokamak Energy and Massachusetts-based Commonwealth Fusion Systems, or CFS, are tokamaks, a Russian acronym describing a toroidal chamber in which a ring of high-temperature plasma is contained within a spiral magnetic field. Reactors such as JET or ITER are also tokamaks, and among the many challenges facing a tokamak designer is the stable creation and maintenance of that field. In this, the new tokamaks have an ace up their sleeve, in the form of a high-temperature superconducting tape from which those super-powerful magnets can be constructed. This makes the magnets easier to make, cheaper to maintain at their required temperature, and smaller than the low-temperature superconductors found in previous designs.

The world of nuclear fusion is a particularly exciting one to follow in these times of climate crisis, with competing approaches from laser-based devices racing with the tokamak projects to produce the research which will eventually lead to safer carbon-free power. If the CFS or Tokamak Energy reactors lead eventually to a fusion power station on the edge of our cities then it may just be some of the most important work we’ve ever reported.