Turning trash into art is something we undoubtedly all admire. [Davis DeWitt] did just that with a massive mural made entirely from discarded receipt paper. [Davis] got lucky while doing some light dumpster diving, where he stumbled upon the box of thermal paper rolls. He saw the potential them and, armed with engineering skills and a rental-friendly approach, set out to create something original.

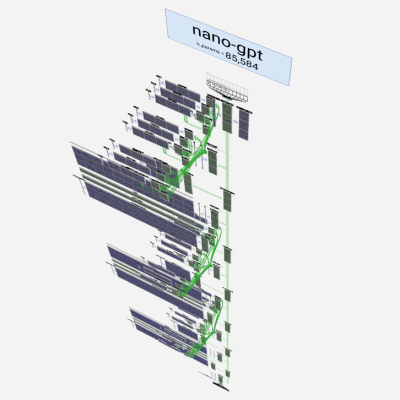

The journey began with a simple test: how long can a receipt be printed, continuously? With a maximum length of 10.5 feet per print, [Davis] designed an image for the mural using vector files to maintain a high resolution. The scale of the project was a challenge in itself, taking over 13 hours to render a single image at the necessary resolution for a mural of this size. The final piece is 30 foot (9.144 meters) wide and 11 foot (3.3528 meters) tall – a pretty conversational piece in anyone’s room – or shop, in [Davis]’ case.

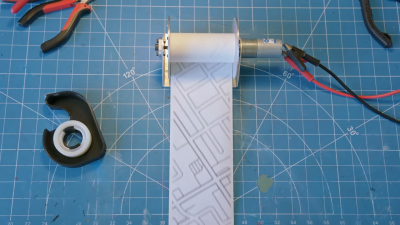

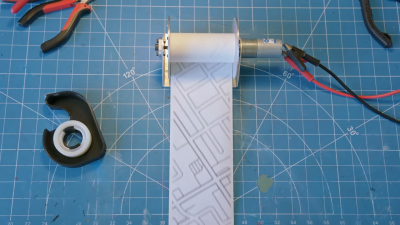

Once the design was ready, the image was sliced into strips that matched the width of the receipt paper. Printing over 1,000 feet of paper wasn’t without its issues, so [Davis] designed a custom spool system to undo the curling of the receipts. Hanging the mural involved 3D-printed brackets and binder clips, allowing the strips to hang freely with a kinetic effect.

Though the thermal paper will fade over time, the beauty of this project lies in its adaptability—just reprint any faded strips. Want to see how it all came together? Watch the full process here.

Continue reading “Massive Mural From Thermal Receipt Paper” →