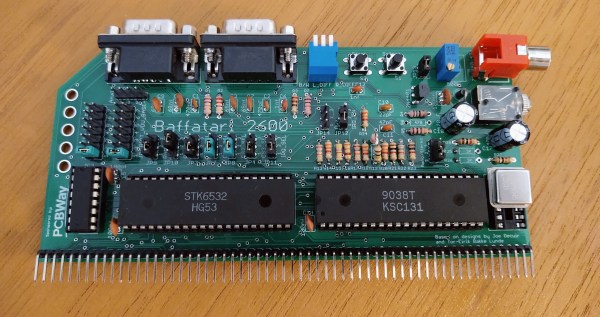

Retro hardware often looks fantastic, but we may find we no longer need it for its original function. [John Anderson] found that to be the case with some old Heathkit gear, and set about giving them a fun overhaul.

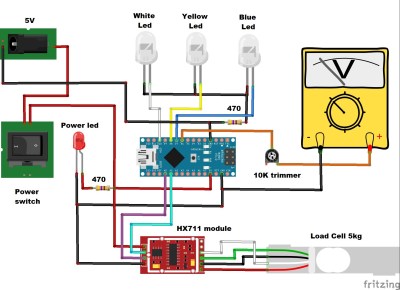

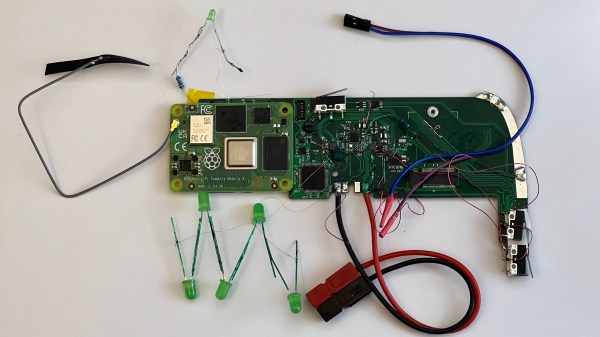

With the help of AVR microcontrollers, the devices have been repurposed into electronic dice towers for playing Dungeons & Dragons. A seed is generated based on the chip’s uptime, and supplied to a pseudorandom number generator that emulates dice rolls. The devices can be configured to roll a variety of dice, including the usual 6, 8, 10, and 20-sided varieties. Plus, they can be set to roll multiple dice at a time — useful when you’re rolling complicated spells and attacks in combat.

[John] has converted a variety of Heathkit devices, from Morse code trainers to digital multi-meters. They provide their beautiful cases and a great retro aesthetic, and we think they’d make fitting table decoration for retro cyberpunk tabletop games, too.

Creating your own electronic dice is a great way to get familiar with programming microcontrollers. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize 2022: Digital Dice Towers Built In Beautiful Retro Cases”