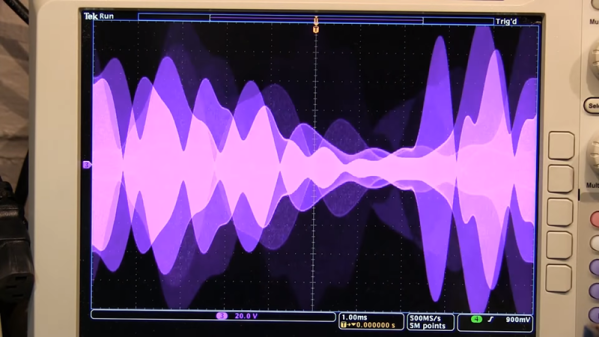

There was a time — not long ago — when radio and even wired communications depended solely upon Morse code with OOK (on off keying). Modulating RF signals led to practical commercial radio stations and even modern cell phones. Although there are many ways to modulate an RF carrier with voice AM or amplitude modulation is the oldest method. A recent video from [W2AEW] shows how this works and also how AM can be made more efficient by stripping the carrier and one sideband using SSB or single sideband modulation. You can see the video, below.

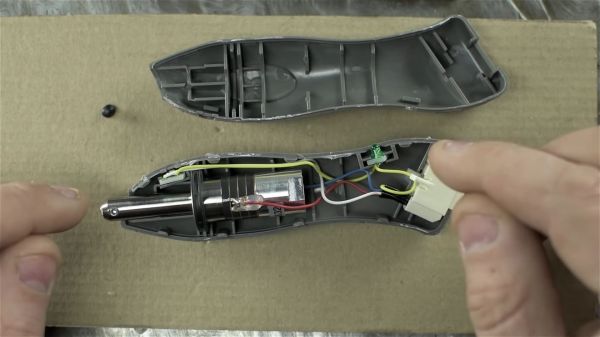

As is typical of a [W2AEW] video, there’s more than just theory. An Icom transmitter provides signals in the 40 meter band to demonstrate the real world case. There’s discussion about how to measure peak envelope power (PEP) and comparison to average power and other measurements, as well.