[Hannah] is restoring a 1962 Volkswagen Bug. The goal is to get the car on the road in time for her driver’s test. This is no easy task, as the lower 3 inches of all the body work is rusted out, and the engine is…. well, missing. Basically, the car needs a frame off restoration. This means that [Hannah] will have a lot of metal bodywork to clean up. One of the easiest ways to do that is sandblasting.

Large scale sandblasting is a bit different from most air-powered operations. Sandblasting needs only a modest air pressure, but a high air flow. [Hannah] need 25 Sustained Cubic Feet Per Minute (SCFM) at 80 PSI for sandblasting. Most compressors can easily supply that pressure, but 25 SCFM is asking quite a lot. She could go with an expensive 3 phase unit, or rent a diesel screw compressor. However, [Hannah] decided to connect 4 compressors in parallel to give her the flow she needed.

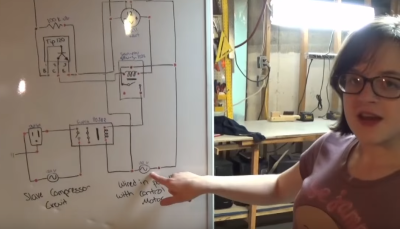

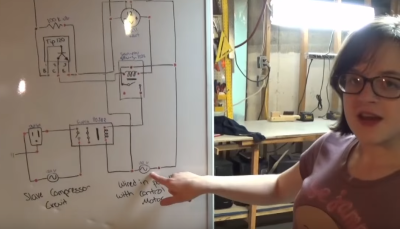

Connecting the air outputs in parallel is easy. The problem is the electricity. Each compressor is rated for 9 amps while running. They draw quite a bit more while starting up. The compressors have to be wired to individual 15 amp circuits to avoid blowing fuses. They also need to be started in sequence so they don’t pull down the AC for the entire house while starting.

Hannah could have used any sort of delay for this, but she chose an Arduino. The Arduino’s wall wart is wired up to the master compressor. Turning on the master powers up the Arduino which immediately starts a 2 second delay. When the delay times out, the Arduino fires up the second compressor. After several delay loops, all 4 compressors are running together.

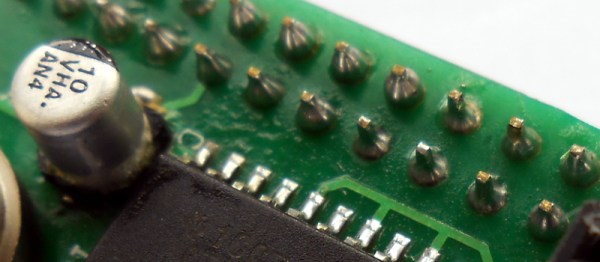

The Arduino’s GPIO pins can’t handle 9 amp AC loads, so [Hannah] wired them to TIP120 transistors. The TIP120s drive low power relays, which in turn drive high current air conditioning relays. The system works quite well, as can be seen in the video below the break.

The Arduino’s GPIO pins can’t handle 9 amp AC loads, so [Hannah] wired them to TIP120 transistors. The TIP120s drive low power relays, which in turn drive high current air conditioning relays. The system works quite well, as can be seen in the video below the break.

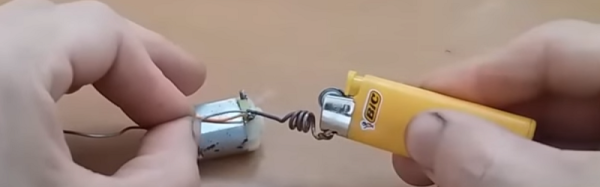

If you’re interested in air compressor projects, check out this setup made from an old refrigerator compressor. For more background on the TIP120, check out this article about these useful transistors.

Continue reading “Parallel Compressors For Sandblasting Without Crashing Your Grid” →

The Arduino’s GPIO pins can’t handle 9 amp AC loads, so [Hannah] wired them to TIP120 transistors. The TIP120s drive low power relays, which in turn drive high current air conditioning relays. The system works quite well, as can be seen in the video below the break.

The Arduino’s GPIO pins can’t handle 9 amp AC loads, so [Hannah] wired them to TIP120 transistors. The TIP120s drive low power relays, which in turn drive high current air conditioning relays. The system works quite well, as can be seen in the video below the break.