Epoxy is a great and useful material typically prepared by mixing two components together. But often we find ourselves mixing too much epoxy for the job at hand, and we end up with some waste left behind. [Keith Decent’s] utility mat aims to make good use of what is otherwise waste material.

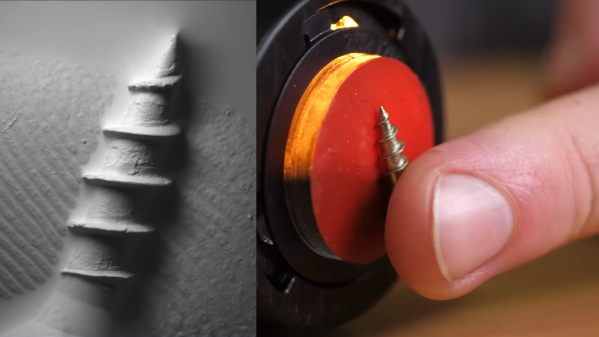

The concept is simple yet ingenious. It’s a flexible mat that serves as a mold for all kinds of simple little plastic workshop tools. The idea is that when you have some epoxy left over from pouring a finish on a table or laying up some composites, you can then pour the excess into various sections of the utility mat. The epoxy can then be left to harden, producing all manner of useful little tools.

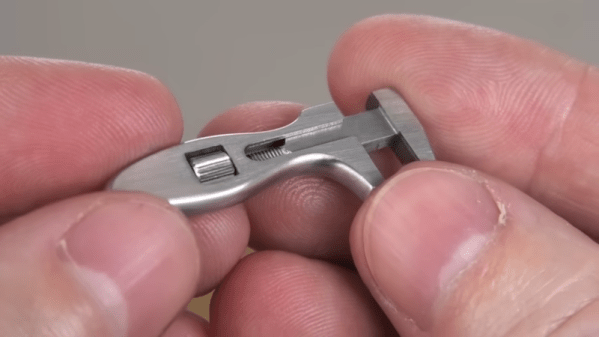

It may seem silly, but it could save your workshop plenty of nickels and dimes. Why keep buying box after box of stir sticks when you can simply make a few with zero effort from the epoxy left from your last job? The utility mat also makes other useful nicknacks like glue spreaders, scrapers, wedges, and painter’s pyramids.

We’ve seen other great recycling hacks over the years too. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Utility Mat Turns Waste Epoxy Into Useful Tools”