Even if you wouldn’t describe yourself as a history buff, you’re likely familiar with the Enigma machine from World War II. This early electromechanical encryption device was used extensively by Nazi Germany to confound Allied attempts to eavesdrop on their communications, and the incredible effort put in by cryptologists such as Alan Turing to crack the coded messages it created before the end of the War has been the inspiration for several books and movies. But did you know that there were actually several offshoots of the “standard” Enigma?

For their entry into the 2019 Hackaday Prize, [Arduino Enigma] is looking to shine a little light on one of these unusual variants, the Enigma Z30. This “Baby Enigma” was intended for situations where only numerical data needed to be encoded. Looking a bit like a mechanical calculator, it dropped the German QWERTZ keyboard, and instead had ten buttons and ten lights numbered 0 through 9. If all you needed to do was send off numerical codes, the Z30 was a (relatively) small and lightweight alternative for the full Enigma machine.

For their entry into the 2019 Hackaday Prize, [Arduino Enigma] is looking to shine a little light on one of these unusual variants, the Enigma Z30. This “Baby Enigma” was intended for situations where only numerical data needed to be encoded. Looking a bit like a mechanical calculator, it dropped the German QWERTZ keyboard, and instead had ten buttons and ten lights numbered 0 through 9. If all you needed to do was send off numerical codes, the Z30 was a (relatively) small and lightweight alternative for the full Enigma machine.

Creating an open source hardware simulator of the Z30 posses a rather unique challenge. While you can’t exactly order the standard Enigma from Digi-Key, there are at least enough surviving examples that they’ve been thoroughly documented. But nobody even knew the Z30 existed until 2004, and even then, it wasn’t until 2015 that a surviving unit was actually discovered in Stockholm.

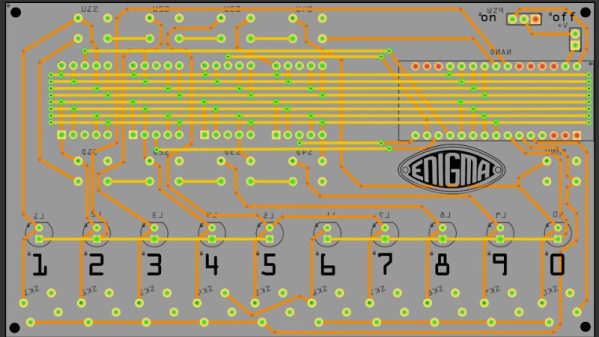

Of course, [Arduino Enigma] does have some experience with such matters. By modifying the work that was already done for full-scale Enigma simulation on the Arduino, it only took a few hours to design a custom PCB to hold an Arduino Nano, ten buttons with matching LEDs, and of course the hardware necessary for the iconic rotors along the top.

The Z30 simulator looks like it will make a fantastic desk toy and a great way to help visualize how the full-scale Enigma machine worked. With parts for the first prototypes already on order, it shouldn’t be too long before we get our first good look at this very unique historical recreation.