For those getting started with 3D printers, thermoplastics such as ABS and PLA are the norm. For those looking to produce parts with some give, materials like Ninjaflex are most commonly chosen, using thermoplastic polyeurethane. Until recently, it hasn’t been possible to 3D print latex rubber. However, a team at Virginia Tech have managed the feat through the combination of advanced printer hardware and some serious chemistry.

The work was primarily a collaboration between [Phil Scott] and [Viswanath Meenakshisundaram]. After initial experiments to formulate a custom liquid latex failed, [Scott] looked to modify a commercially available product to suit the project. Liquid latexes are difficult to work with, with even slight alterations to the formula leading the solution to become unstable. Through the use of a molecular scaffold, it became possible to modify the liquid latex to become photocurable, and thus 3D printable using UV exposure techniques.

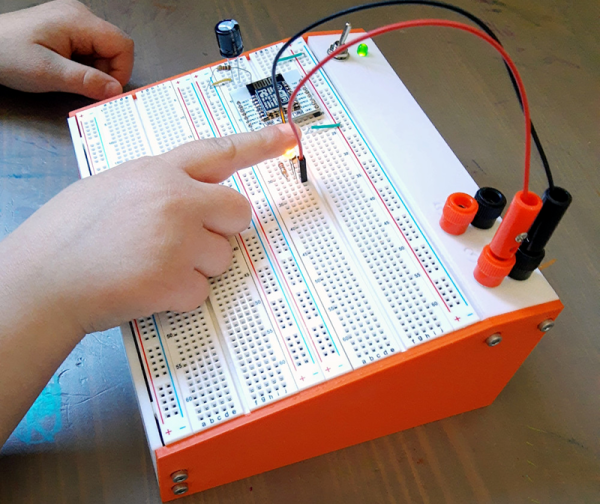

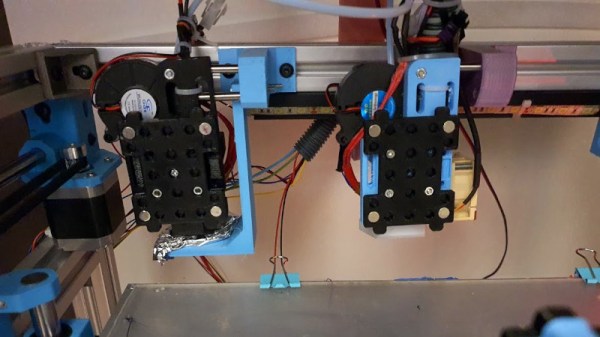

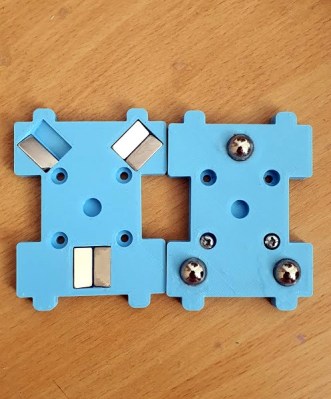

The printer side of things took plenty of work, too. After creating a high-resolution UV printer, [Meenakshisundaram] had to contend with the liquid latex resin scattering light, causing parts to be misshapen. To solve this, a camera was added to the system, which visualises the exposure process and self-corrects the exposure patterns to account for the scattering.

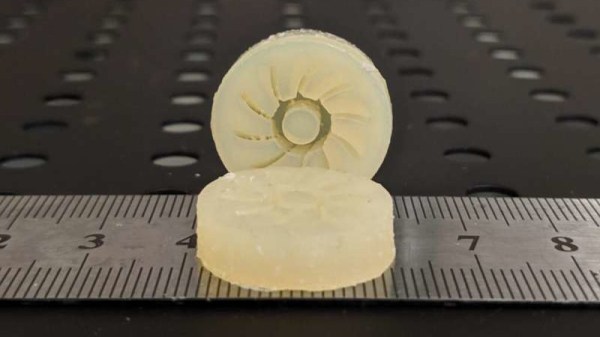

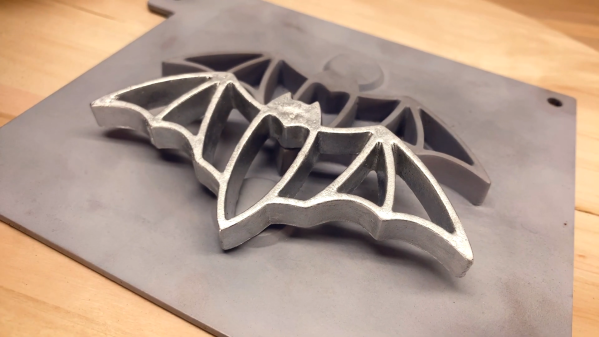

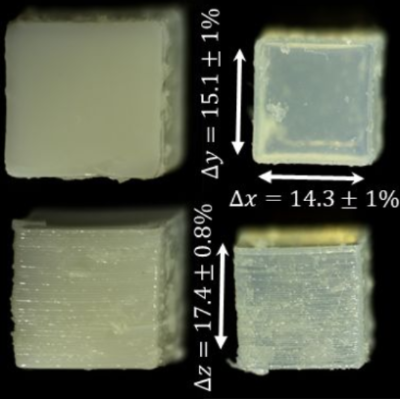

It’s an incredibly advanced project that has produced latex rubber parts with advanced geometries and impressive mechanical properties. We suspect this technology could be developed quickly in the coming years to produce custom rubber parts with significant strength. In the meantime, replicating flexible parts is still possible with available filaments on the market.

[via phys.org]