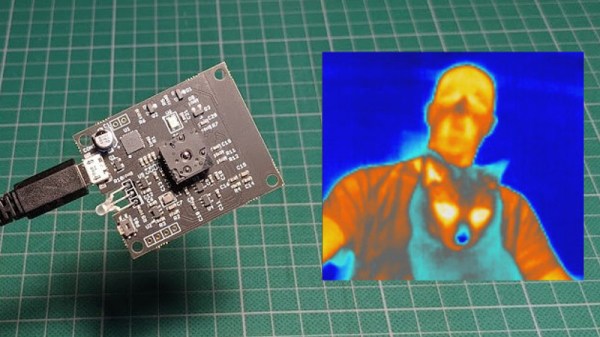

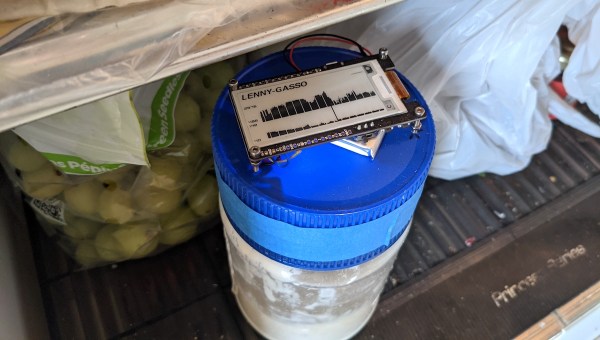

A thermal camera is a tool I have been wanting to add to my workbench for quite a while, so when I learned about the tCam-Mini, a wireless thermal camera by Dan Julio, I placed an order. A thermal imager is a camera whose images represent temperatures, making it easy to see things like hot and cold spots, or read the temperature of any point within the camera’s view. The main (and most expensive) component of the tCam-Mini is the Lepton 3.5 sensor, which sits in a socket in the middle of the board. The sensor is sold separately, but the campaign made it available as an add-on.

Want to see how evenly a 3D printer’s heat bed is warming up, or check whether a hot plate is actually reflowing PCBs at the optimal temperature? How about just seeing how weird your pets would look if you had heat vision instead of normal eyes? A thermal imager like the tCam-mini is the tool for that, but it’s important to understand exactly how the tCam-mini works. While it may look like a webcam, it does not work like one.

Continue reading “Hands-On Review: TCam-Mini WiFi Thermal Imager”