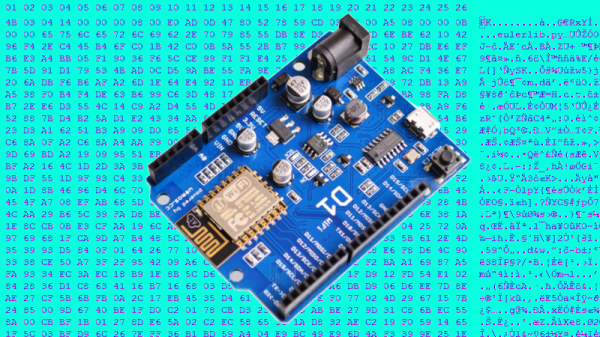

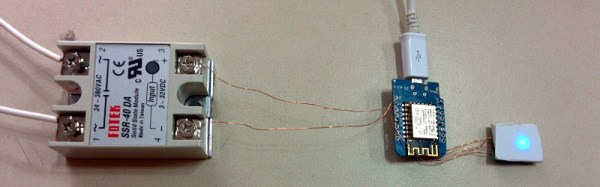

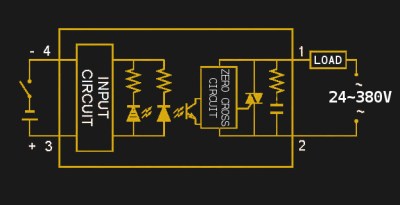

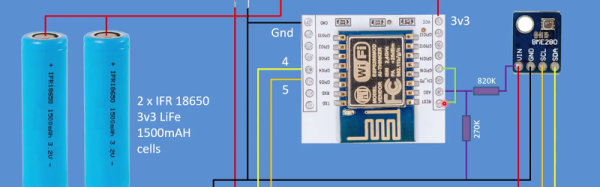

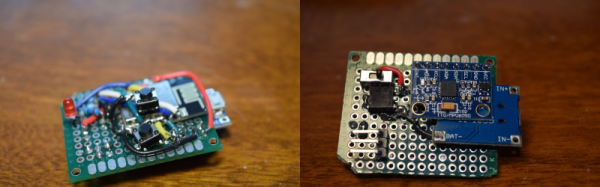

[Pete] was building a hot tub controller, using a WEMOS board based on the venerable ESP8266. After assembly, the board was plugged into USB and [Pete] hit the flash button. No dice. Investigation with some terminal software indicated a checksum error.

Assuming the board was dead, [Pete] grabbed another — and suffered the same problem. The WEMOS boards wouldn’t program, but other boards had no issues. Sensing that something may be amiss, further research was in order. A forum post turned up discussing different programming modes for the ESP8266.

It turns out that there are different types of flash used with the ESP8266, and the correct programming mode must be selected for a given hardware setup. These modes are known as DIO and QIO, meaning “dual IO” and “quad IO” respectively. This refers to the number of IO line used to talk to the flash memory. There are also further modes, known as DOUT and QOUT. It’s important to identify the modes supported by the flash chip on board, by looking at the datasheet. Obviously this can be difficult on some pre-built modules, so experimentation is the key here.

With the wrong mode selected, writes to the flash will fail, and reading back will turn up a checksum error. It’s a simple matter of changing a line in the make file and trying different modes, to see which one works. This forum post has a more in-depth coverage of the issue.

By choosing different flash memory parts and selecting the DIO or DOUT modes, it’s actually possible to free up more GPIO pins as well. This knowledge is handy when optimizing ESP8266 designs for memory speed or maximum IO flexibility. It’s a good lesson that it always pays to look at the datasheet to get the best out of your parts.