The Arduino is a popular microcontroller platform for getting stuff done quickly: it’s widely available, there’s a wealth of online resources, and it’s a ready-to-use prototyping platform. On the opposite end of the spectrum, if you want to enjoy programming every bit of the microcontroller’s flash ROM, you can start with an arbitrarily tight resource constraint and see how far you can push it. [lucas][Radical Brad]’s demo that can output VGA and stereo audio on an eight-pin DIP microcontroller is a little bit more amazing than just blinking an LED.

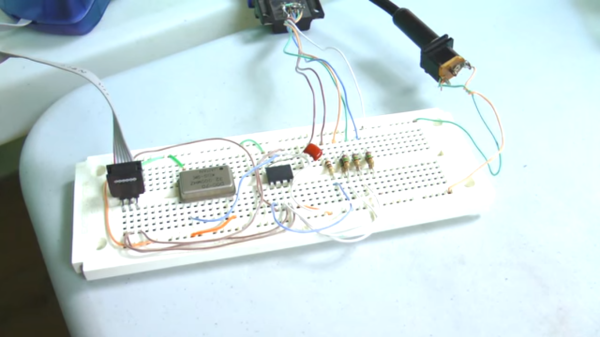

[lucas][RB] is using an ATtiny85, the larger of the ATtiny series of microcontrollers. After connecting the required clock signal to the microcontroller to get the 25.175 Mhz signal required by VGA, he was left with only four pins to handle the four-colors and stereo audio. This is accomplished essentially by sending audio out at a time when the VGA monitor wouldn’t be expecting a signal (and [lucas][Rad Brad] does a great job explaining this process on his project page). He programmed the video core in assembly which helps to optimize the program, and only used passive components aside from the clock and the microcontroller.

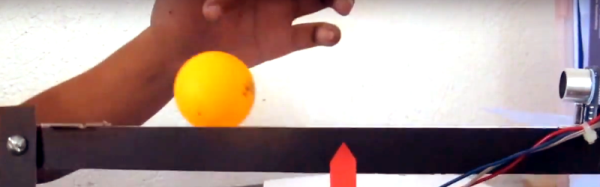

Be sure to check out the video after the break to see how a processor with only 512 bytes of RAM can output an image that would require over 40 KB. It’s a true testament to how far you can push these processors if you’re determined. We’ve also seen these chips do over-the-air NTSC, bluetooth, and even Ethernet.