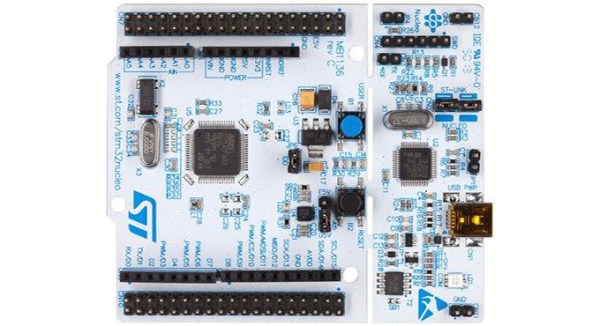

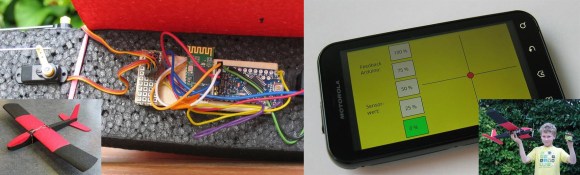

Having a big block of hot to dump current into is a very useful thing to have if you’re testing batteries, power supplies, high power LEDs, electroplating, or any thing else that would normally require a huge resistor. [Jakub] found himself in need of an electronic load, and instead of a transistor and a pot, decided to make something more automatic: a programmable load built around an Arduino shield.

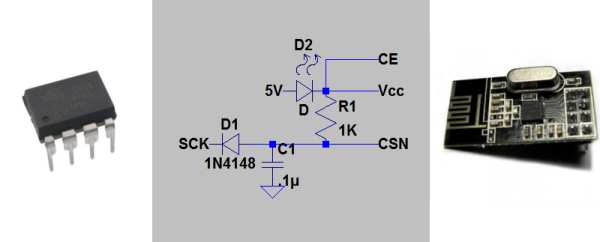

The idea behind this load is pretty simple: connect a device to a FET and shunt resistor to measure current. Drive the gate of the FET with an op-amp that maintains either constant current or constant voltage. Control everything with a DAC, and you have a programmable load controlled by an Arduino.

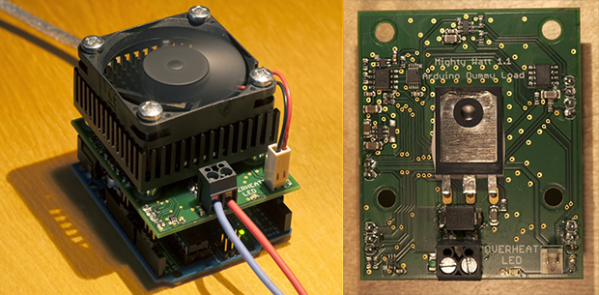

With such a small form factor, getting rid of all that heat was bound to be a problem. For this, [Jakub] is using a 50×50 mm BGA style heat sink with a 5V fan. If it’s good enough for a big CPU, it should be able to handle dumping 70 Watts into a FET. There’s also a conservative application of thermal paste and a very small thermistor underneath the FET that’s able to be read by the Arduino. It might slowly heat up your room, but it’s not going to catch fire.

With the Arduino sketches [Jakub] wrote for his load he was able to characterize a pair of Idea batteries and figure out how much charge a three-year-old recyclable battery had. It’s a great piece of work, and if [Jakub] is willing to go through the hassle of a Kickstarter, it would make a fine crowdfunded product.