Specialized processes require specialized tools and instruments, and processes don’t get much more specialized than the making of semiconductors. There’s a huge industry devoted to making the equipment needed for semiconductor fabrication plants, but most of it is fabulously expensive and out of reach to the home gamer. Besides, where’s the fun in buying when you can build your own fab lab stuff, like this DIY tube oven?

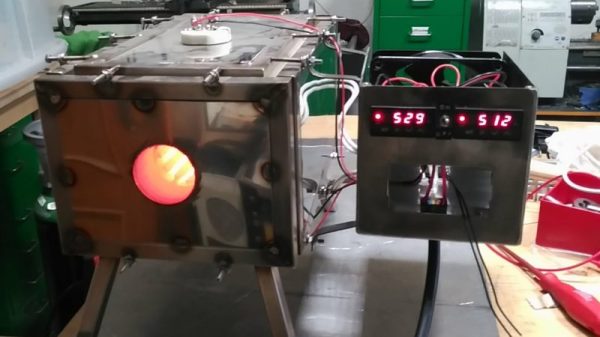

A tube oven isn’t much more complicated than it sounds — it’s just a tube that gets hot. Really, really hot — [Nixie] is shooting for 1,200 °C. Not just any materials will do for such an oven, of course, and this one is built out of blocks of fused alumina ceramic. The cavity for the tube was machined with a hole saw and a homebrew jig that keeps everything aligned; at first we wondered why he didn’t use his lathe, but then we realized that chucking a brittle block of ceramic would probably not end well. A smaller hole saw was used to make trenches for the Kanthal heating element and the whole thing was put in a custom stainless enclosure. A second post covers the control electronics and test runs up to 1,000°C, which ends up looking a little like the Eye of Sauron.

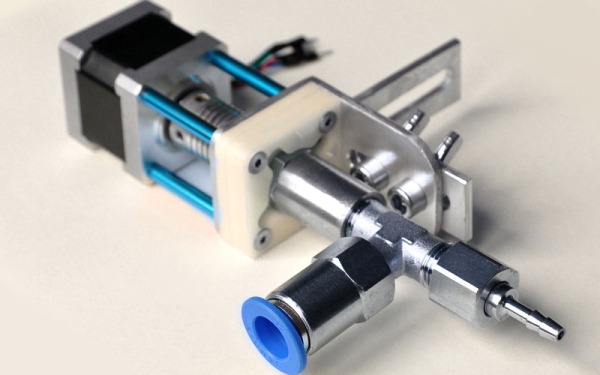

We’ve been following [Nixie]’s home semiconductor fab buildout for a while now, starting with a sputtering rig for thin-film deposition. It’s been interesting to watch the progress, and we’re eager to see where this all leads.