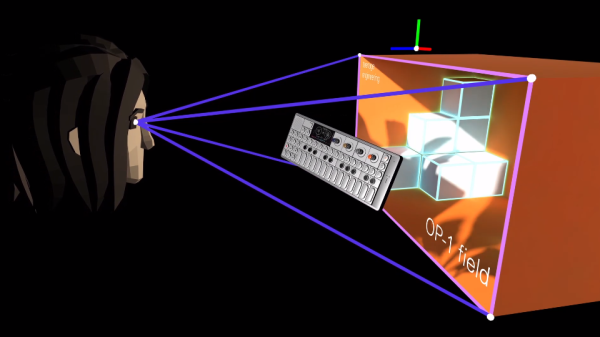

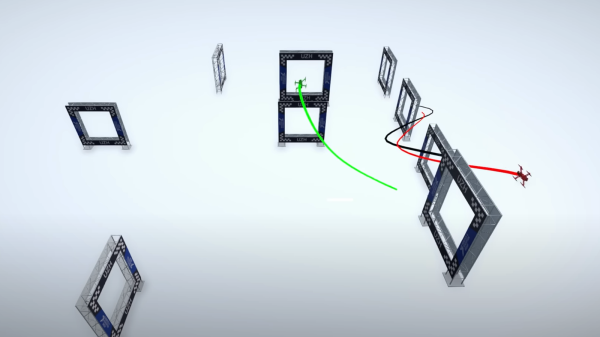

NVIDIA’s Jetson line of single-board computers are doing something different in a vast sea of relatively similar Linux SBCs. Designed for edge computing applications, such as a robot that needs to perform high-speed computer vision while out in the field, they provide exceptional performance in a board that’s of comparable size and weight to other SBCs on the market. The only difference, as you might expect, is that they tend to cost a lot more: the current top of the line Jetson AGX Orin Developer Kit is $1999 USD

Luckily for hackers and makers like us, NVIDIA realized they needed an affordable gateway into their ecosystem, so they introduced the $99 Jetson Nano in 2019. The product proved so popular that just a year later the company refreshed it with a streamlined carrier board that dropped the cost of the kit down to an incredible $59. Looking to expand on that success even further, today NVIDIA announced a new upmarket entry into the Nano family that lies somewhere in the middle.

Luckily for hackers and makers like us, NVIDIA realized they needed an affordable gateway into their ecosystem, so they introduced the $99 Jetson Nano in 2019. The product proved so popular that just a year later the company refreshed it with a streamlined carrier board that dropped the cost of the kit down to an incredible $59. Looking to expand on that success even further, today NVIDIA announced a new upmarket entry into the Nano family that lies somewhere in the middle.

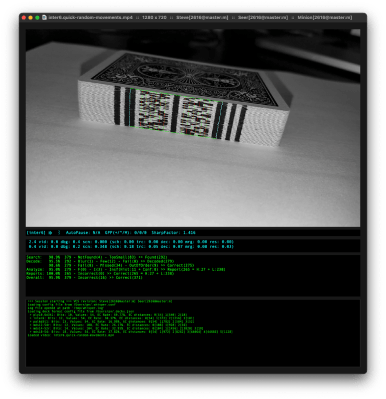

While the $499 price tag of the Jetson Orin Nano Developer Kit may be a bit steep for hobbyists, there’s no question that you get a lot for your money. Capable of performing 40 trillion operations per second (TOPS), NVIDIA estimates the Orin Nano is a staggering 80X as powerful as the previous Nano. It’s a level of performance that, admittedly, not every Hackaday reader needs on their workbench. But the allure of a palm-sized supercomputer is very real, and anyone with an interest in experimenting with machine learning would do well to weigh (literally, and figuratively) the Orin Nano against a desktop computer with a comparable NVIDIA graphics card.

We were provided with one of the very first Jetson Orin Nano Developer Kits before their official unveiling during NVIDIA GTC (GPU Technology Conference), and I’ve spent the last few days getting up close and personal with the hardware and software. After coming to terms with the fact that this tiny board is considerably more powerful than the computer I’m currently writing this on, I’m left excited to see what the community can accomplish with the incredible performance offered by this pint-sized system.

Continue reading “Hands-On: NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano Developer Kit”